BUDDY & JESUS: THE FAITH OF BUDDY HOLLY by Johnny J. Blair

Optimism and yearning aroused one of America’s most celebrated art-forms: rock’n’roll. It, along with rhythm’n’ blues, was birthed from big band jazz, blues, country, folk, pop and, perhaps more than anything, gospel. The harmony-coated spirituals and hard-driving worship songs certified the chord patterns and rhythms that breathed life into all these styles.

In the 1950s, a rebounding post-war economy allowed young people to experience freedoms their parents never knew. People were drawn to cross the color line as radios brought rhythm’n’blues into the homes of white teenagers and a rising civil rights movement fueled, in part, by churches. From the back doors of “black churches” to back-alley nightclubs inMemphis and New Orleans, rock’n’roll found its face.

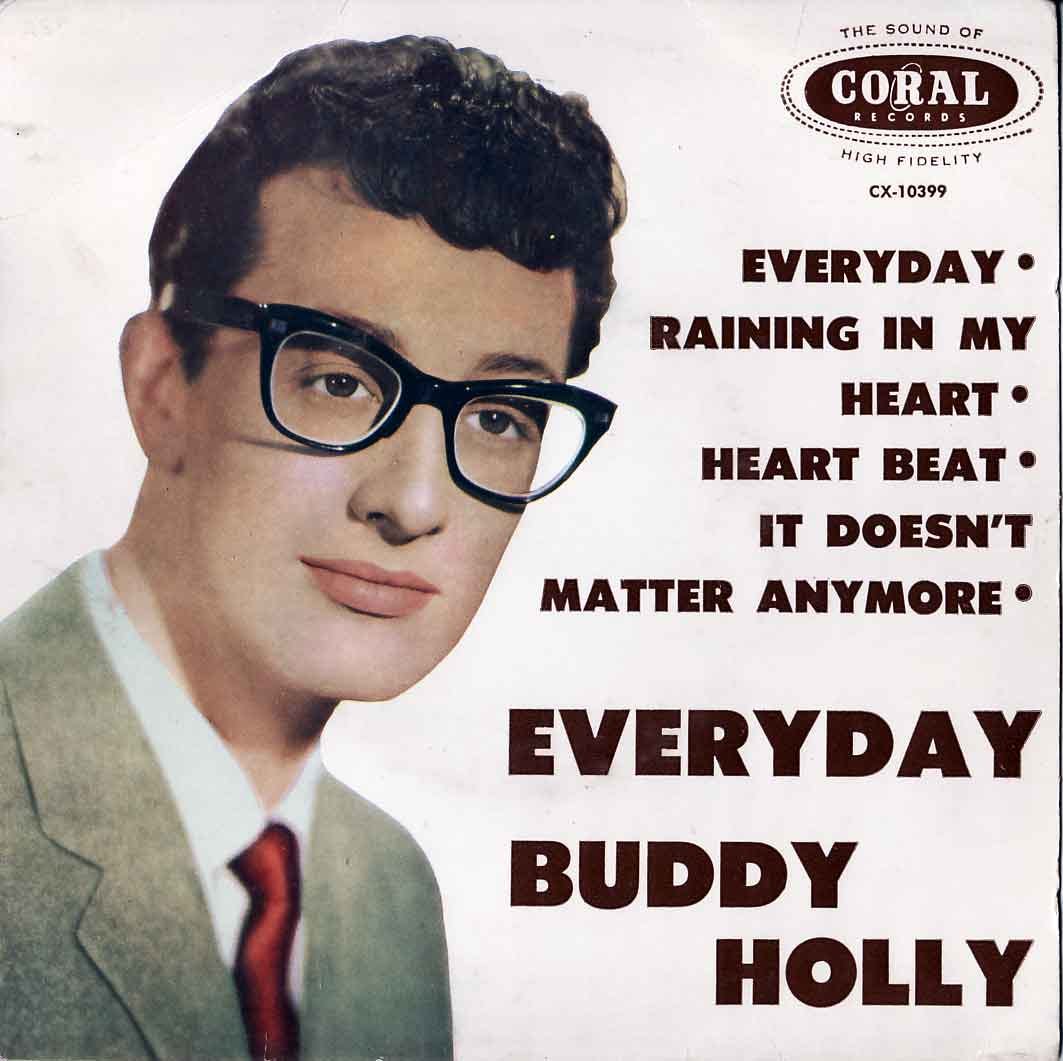

Buddy Holly was one of the great pioneers of rock’n’roll, if not in all popular music from that time on. He experimented with eclectic styles and branded his own sound. His songs are now American classics and scores of artists cover his music. He was one of the first independents to produce hit records without the aid or controls of huge record companies. In the heat of showbiz, glamor and sex appeal are the big lures, but genuine humanity is what endures, and Holly had that endurance. He was an everyman who said, “Take me as I am—with big glasses.” He continues to draw an audience years after his death.

Holly was aware of being caught up in the times as he graduated from high school in 1954. To him, music wasn’t just a ticket out of poverty. Music was a release from meaninglessness. Offstage he was businesslike and reserved. Onstage he was like high-voltage lighting. Music was where he found identity and liberation. Loaded with energy and ambition, he was drawn to all kinds of music. Like most people coming of age in the early 1950s, he sought his voice in the panorama of blues and country—then called “hillbilly.” Pop and showtunes were “too grown up” in theme (contrary to urban legend adultery and intoxication were uncommon to kids of the 1950s), and novelty music was disposable. It was just a matter of mixing it up and lyricizing for people his own age. He was often heard to say, “You don’t lose anything by trying.”

Over the years, filmmakers and pop mythologists have inserted fiction into Holly’s story, and one facet of his life has been downplayed: Buddy Holly was a devout Christian—at least according to his family and biographers John Beecher and John Goldrosen (“Remembering Buddy,” Da Capo Press, 1995).

Born Charles Hardin Holley, Buddy (nicknamed by his parents) was raised Baptist. Members of The Crickets (Holly’s back-up band) were all of the same denomination. Holly and his bandmates prayed before important events. In 1957, at the signing of their first major publishing contract following their first big hit “That’ll Be the Day,” they ordered that a percentage of their royalties would go to their home churches. Fame took hold, and Holly and crew were not totally exempt from “the worldy temptations,” but it is said that their behavior was consistently moral and polite. On their tour buses, you’d be more likely to hear spirituals being sung and see Bibles passed around than other “vices of the road.”

Holly’s widow, Maria Elena, tells of his unrealized aim to play everything from jazz to Cajun (he produced Waylon Jennings Cajun-country single “Jole Blon”).

Holly wanted to produce and write more songs for other artists, but had he lived past the infamous plane crash of 1959, gospel music would have been a top priority.

Beginning in 1958, Holly began to study black gospel singers like Mahalia Jackson. He visited studios where gospel artists worked to learn from their arrangements and techniques. He even approached Ray Charles about collaborating on a lushly orchestrated gospel production.

The record industry exploded in the late 1940s. To cover their bases, major labels kept a “gospel division.” It was their job to sell records and the marketing of quality music was not impeded by a separation of “sacred” from “secular” (that would come later in time). Until the late 1960s, it was not unusual for a pop/rock artist to cut a “gospel record” as a tribute to the Christian faith, whether it was a personal expression or a marketing ploy. Concurrently, it was not unusual for a “good Christian” (however you define that) to sing “secular material” so long as they kept up a wholesome image.

To this end, Holly set a fine example. His brother Larry Holley said, “(Buddy) sometimes had doubts about the propriety of his vocation. He never expressed his doubts to anyone outside of his family, but (to us) he talked about his qualms. Music was Buddy’s life, and he neither wanted to nor would have been able to break away from it, but he wanted to feel like he was doing ‘God’s work’ too, even while remaining a secular entertainer. The (planned) gospel album would have been an expression of his own conscience.”

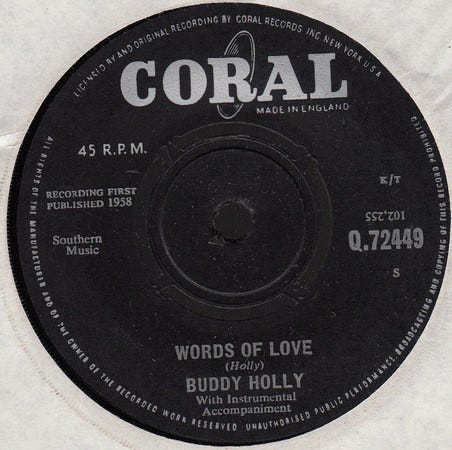

Holly recorded one traditional gospel song in his career—“I Hear You Calling Me Lord” (a 1953 demo). On that count, Holly wouldn’t do well in today’s artificial “contemporary Christian music” scene where artists sign with “Christian record labels” and one’s faith is qualified by reciting rigid, quasi-Biblical slogans. Holly would’ve failed at that. However, there is no lack of spiritual tinting in his material.

The title of the song “Well...All Right”—rated by fans to be one of Holly’s prime cuts—comes from an affirmation used by pentacostal preachers (the same phrase induced A.J. Reynolds to write “Jesus Is Just Alright With Me,” popularized years later by The Byrds, DC Talk and The Doobie Brothers). Holly picked up the phrase from another pentacostal, Little Richard.

“Well...All Right” is one of Holly’s most distinctive and innovative recordings (oddly, he considered it B-side material). The instrumental section is graceful and understated, and the lyrics intone the hope and uncertainty that summarizes adolescence. Yet, a timeless quality suggests a connection with the eternal:

“Well all right, so I’m being foolish/well all right let people know/about the dreams and wishes that you wish/in the nights when lights are low...

“Well all right, so I’m going steady/it’s all right, let people say/that those foolish kids can’t be ready/for the love that comes their way...

“Well all right, Well all right/we will live and love with all our might/Well all right, Well all right, Well all right/You know our lifetime love will be all right”

Interestingly, Blind Faith would cover “Well...All Right” and sequence it between “Can’t Find My Way Home” and “Presence of the Lord”—songs described as “hymns of desperation.”

Converting hymns into pop songs was not new, and, in 1958, Holly wrote one of his greatest ballads, “True Love Ways,” on a melody partially based on “I’ll Be All Right”—a black gospel hymn recorded (circa 1951) by The Angelic Gospel Singers. Holly loved this record (it was one of the selections performed at his funeral). In keeping with the primary inspiration, the lyrics of “True Love Ways” convey a sense of acceptance, faith, and patience.

These and similar virtues inform the work of Holly. Beginning with “That’ll Be the Day” and working through “Everyday” and into other titles, Holly wrote from a lexicon of resilience, honesty, and Biblical truth. “Peggy Sue” can’t compare to the poetry of Song of Solomon, but “Peggy Sue” sent a robust romantic equation into a pop milieu lacking in joyful innocence. Eventually, “Peggy Sue Got Married”—Peggy Sue became the wife of fellow-Cricket, Jerry Allison.

Christianity had a strange but undeniable presence in rock’n’roll and rhythm’n’blues. The early architects of this music—Johnny Cash, Sam Cooke, the Everly Brothers, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, Elvis Presley, Little Richard Penniman and (to be totally fair) Pat Boone—cited the music of the church as an all-important influence. These touchstone artists routinely “confessed Christ” as their “Lord and Savior.”

Cash and Presley had their own sets of demons, but, like Holly, the musical watershed of the church shaped their music. Both Cash and Presley released several “gospel albums” (Presley wanted to do nothing but gospel but his manager, Colonel Parker, forbade it). Cash built a catalog of narrative songs which, if not Bible-based, were certainly shaped by scripture.

A career in “worldly music” was scorned by fundamentalists, and some artists—most vocally, Jerry Lee Lewis and Little Richard—were seriously conflicted about “doing the devil’s work.” For them, “lifestyle demons” overshadowed the image of “good Christian.” Both men were tortured by a hatred of hypocrisy and a weakness for vices. Sometimes the reaction was melodramatic—Penniman (along with Pat Boone) broke away from “showbiz” to go into ministry.

Upon further study, detachment from the entertainment business is just as much doctrinal as emotional. Lewis and Penniman came from fundamentalist churches that rejected intellectualism and expected their members to remove themselves from mainstream culture. Churches based on liberal theology were just as chilly towards these “young rebels.” For some, rock’n’roll may have been “satanic” and “music to steal hubcaps by,” but rioting, thievery and promiscuity were around before the fifties, and everyone has, at one time or another, opened Pandora’s Box. Like Fats Domino said, “Kids just want to have fun. They don’t want to hurt anybody.”

In reality, the 1950s was a complex and sensitive time for politics and morals. Yet, compared to the arms race, rock’n’roll was a small threat and only a minority of (mainly backwater) churches and racist groups rose against it—albeit loudly. Hollywood and social revisionists have done much to portray Christians as “repressive” when, in fact, churches commonly sponsored teen activities (in England, young John Lennon and Paul McCartney rehearsed in a church basement and performed in church events). Holly, in his musical endeavors, was fully supported by his pastor and his family (as was Cash, Cooke, Presley, et. al.). Rock’n’roll was a threat only to those who were insecure in their own beliefs.

Revisiting the role of Christians in the civil rights movement—in 1957, Holly and the Crickets were the only “white act” (accidentally) booked on a package tour with all black artists (The Clover, The Drifters). Not only were “the white guys” warmly received, but Holly was also one of the first pop artists to publicly challenge segregation laws.

Don McLean eulogized Holly in the mega-hit “American Pie,” but did the music really die? Did “the Father, Son and the Holy Ghost” really “catch the last train for the coast?” Rock’n’roll outlasted the Cold War. Most Communists hated rock’n’roll. We’re still the only nation on earth that has never made a tyrant who tells people how to worship (or not). Along with country and jazz, rock’n’roll is a soundtrack for what makes America great. Holly’s music clarifies this, and his life is a testimony on the impact one Christian can have in his chosen field. In the current state of hyper-secularized pop culture, where faith is marginalized and/or caricaturized, we could use all the Buddy Hollys we can get. (Republished Substack article from 9/7/22).

#buddyholly #crickets #christianity #jesuschrist #baptist #rocknroll #littlerichard #johnnycash #elvispresley #jerryleelewis #popmusic #johnnyjblair