The Record No One Could Stop: BITTER TEARS by Johnny Cash

60 Years of a raw American statement by The Man in Black

Racism, censorship, fear, resistance, and even sabotage from the music industry couldn’t stop Johnny Cash from making the album BITTER TEARS: BALLADS OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN, released 60 years ago on October 26th, 1964.

It is one of Cash’s most daring and minimalist works, elegant but raw—the album closer, “The Vanishing Race,” consists of a single tom tom drum, sparse acoustic guitar, and vocal. Where Cash’s previous Americana albums revered cowboys and Western pioneers, BITTER TEARS is a vivid expose. It's stark and moving, and arguably his best Americana album of the Sixties.

The album was also a launch point for my lifelong interest in the anthropology, history, and mythology of American Indians (going back to the Anasazi and my fan-dom of Tony Hillerman novels). It is country music scented by sage, sawdust, and the sweat of cotton pickers, sharecroppers, and sheep herders, stopping at the Last Chance gas station on a two-lane desert highway.

The rough road to BITTER TEARS began on May 10, 1962 as Cash made a highly-anticipated New York debut at Carnegie Hall. He’d been struggling with substances and, instead of impressing the pundits, he bombed. His voice was hoarse and garbled in the mix, and he left the stage deeply depressed. Afterward, a friend suggested Cash take his mind off the gig, and they headed to Greenwich Village’s Gaslight Café.

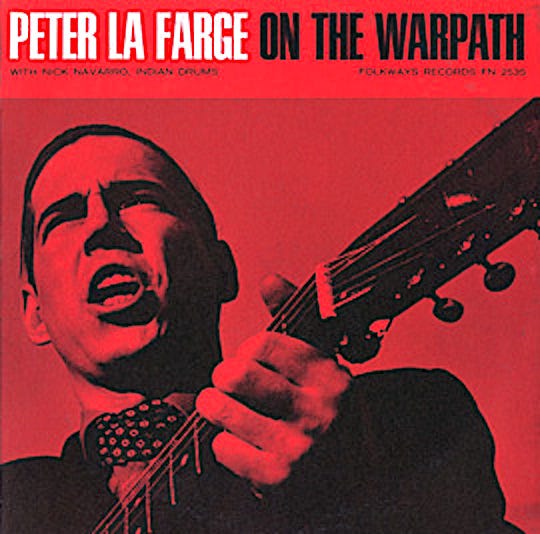

Onstage was protest balladeer Peter La Farge, performing “Ballad of Ira Hayes.”

La Farge was a former rodeo cowboy, playwright, actor, and Navy intelligence operative—plus he was the son of Native activist and novelist Oliver La Farge, who had won a Pulitzer Prize for his Navajo love story, LAUGHING BOY.

Until that time, Cash tended to not mix in politics, opting to talk about uniting people and the dignity of honest work. He empathized with outsiders, convicts, the poor, and Native Americans. However, his identification with Indians was especially deep — even delusional. During the depths of his drug abuse, he convinced himself, and others, that he was Native American himself, with both Cherokee and Mohawk blood (he would later recant this claim as his genealogy revealed only Scottish and English ancestry.)

At the Gaslight, after listening to “Ira Hayes” and La Farge’s other Indian protest tunes, Cash was fixated. “Johnny wanted more than the hillbilly jangle,” La Farge would write later about meeting Cash. “He was hungry for the depth and truth… Johnny has the heart of a folksinger in the purest sense.” Hearing “Ira Hayes” launched Cash into a serious study of Native American history.

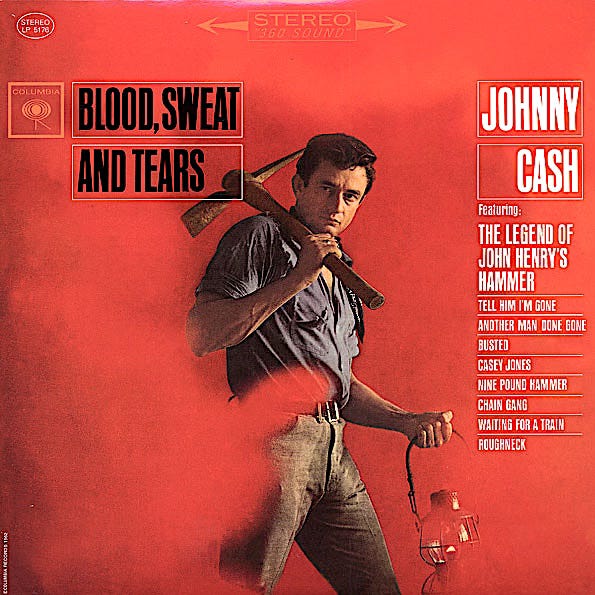

Cash, fresh off the biggest successes of his career, began recording a rather different album. He was alternating folky albums like BLOOD, SWEAT AND TEARS (a celebration of the working man), with marketable discs laden with radio-ready singles.

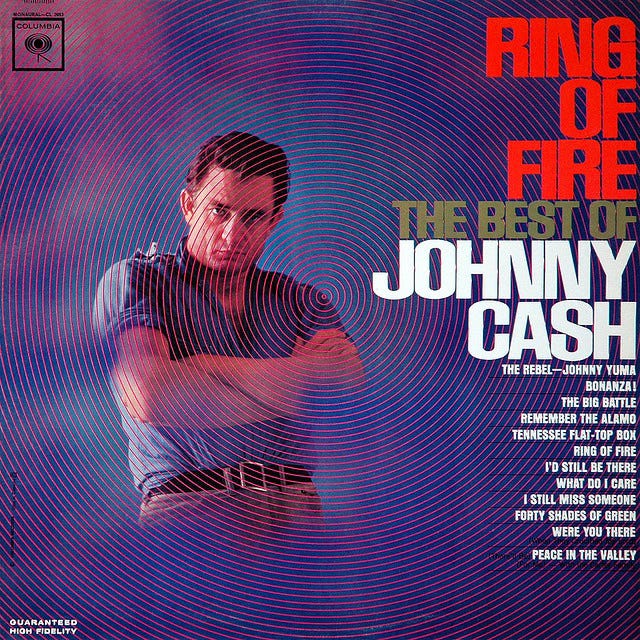

“Ring of Fire” which had reached Number One on the country charts and had crossed over to pop, had bought him the permission of Columbia Records to make an album of “Indian protest songs.”

As Cash explained, “I dove into primary and secondary sources, immersing myself in the tragic stories of the Cherokee and the Apache, among others, until I was almost as raw as Peter. By the time I recorded the album I carried a heavy load of sadness and outrage.”

With the Apache tear necklace draped around his neck, Cash recorded five of La Farge’s songs, two of his own, and one he’d co-written with Johnny Horton. “When we went back into the studio to record what became BITTER TEARS,’” Cash bassist Marshall Grant said, “we could see that John really had a special feeling for this record and these songs.”

“I know that a lot of people into Johnny Cash weren’t into BITTER TEARS,” explains Dick Weissman, a folksinger, ex-member of The Journeymen, and friend of La Farge. “They wanted a “Ballad of a Teenage Queen,” not “Ballad of Ira Hays.” They didn’t want songs about how American’s mistreated Indians.”

Starting in January 1964, Cash kept scoring Number Ones after the country single “Understand Your Man” and the country album I WALK THE LINE. Yet, radio stations wouldn’t play the “Ira Hayes” single, and Columbia refused to promote it. According to John Hammond, legendary producer (and Cash champion) who worked at Columbia, executives at the label didn’t think it had commercial potential. Billboard, the music industry trade magazine, wouldn’t review it.

An editor of a country music magazine demanded that Cash resign from the Country Music Association because “you and your crowd are just too intelligent to associate with plain country folks, country artists and country DJs.” Johnny Western, a DJ, singer, and actor who was part of Cash’s road show, recalls a conversation with “a very popular and powerful DJ.” According to Western, the DJ was “connected to many of the music associations and influential recording industry groups. He had always been incredibly supportive of John.” Western and the DJ started discussing BITTER TEARS and the “Ira Hayes” single. “He asked me why John did this record. I told him that John and all of us had a great feeling for the American Indian cause. He responded that he felt that the music, in his mind, was un-American and that he would never play the record on air and had strongly advised other DJs and radio stations to do the same. ‘Just ignore it until John came back to his senses,’ is what he told me.”

“When John was attacked for “Ira Hayes” and then BITTER TEARS,” recalled Grant, “it just ripped him apart. Hayes was forced to drink by the abuse and treatment of white people who used and abandoned him. To us, it meant Hayes was being tortured and that’s the story we told and it’s true.”

Cash would have the last word. He composed a letter to the entire record industry and placed it in Billboard as a full-page ad on August 22, 1964.

“D.J.’s — station managers — owners, etc.,” demanded Cash, “Where are your guts? These lyrics take us back to the truth … you’re right! Teenage girls and Beatle record buyers don’t want to hear this sad story of Ira Hayes … This song is not of an unsung hero.” Cash slammed the record industry for its cowardice, “Regardless of the trade charts — the categorizing, classifying, and restrictions of air play, this not a country song, not as it is being sold. It is a fine reason though for the gutless to give it a thumbs down.”

Cash demanded that the industry explain its resistance to his single. “I had to fight back when I realized that so many stations are afraid of Ira Hayes. Just one question: WHY???” And then Cash answered for them. “‘Ira Hayes’ is strong medicine …”

Later, Cash explained, “I talked about them wanting to wallow in meaninglessness and their lack of vision for our music. Predictably enough, it got me off the air in more places than it got me on.” In reality, however, as Cash noted in his letter, “Ira Hayes” was already outselling many country hits. It was also a stunning recording. The chorus pairs brutally honest lyrics with a catchy melody, as if Johnny Mercer or Cole Porter wrote topical folk songs:

“Call him drunken Ira Hayes he won’t answer anymore,

Not the whiskey drinkin’ Indian or the Marine that went to war.”

The Carter Family harmonizes through a mist of eerie reverb. The arrangement is durable and quixotic Cash, backed by his stalwart band, bassist Grant, drummer W.S. Holland, and guitarist Luther Perkins (accompanied by session guitarists Norman Blake and Bob Johnston). Ultimately, in part due to the aggressive promotion by Cash, who personally exhorted the song to disc jockeys he knew, by the end of 1964 “Ira Hayes” reached Number 3 on the country singles charts, and BITTER TEARS peaked at Number 2 on the album charts.

The opening song of BITTER TEARS, "As Long as the Grass Shall Grow” concerns the contemporary loss of Seneca nation land in Pennsylvania and New York (the Cornplanter Tract) due to condemnation for federal construction of a dam in the early 1960s. La Farge's song "Custer" mocks the popular veneration of General George Custer. He was overwhelmingly defeated, in part due to his own errors, by Lakota warriors at Little Big Horn. "The Talking Leaves" tells about Sequoyah inventing written words in 1821, which increased Cherokee literacy. “White Girl” tells of a Native American man falling in love with an unobtainable white woman, a subtext in Tony Hillerman’s novels about Navajo tribal police.

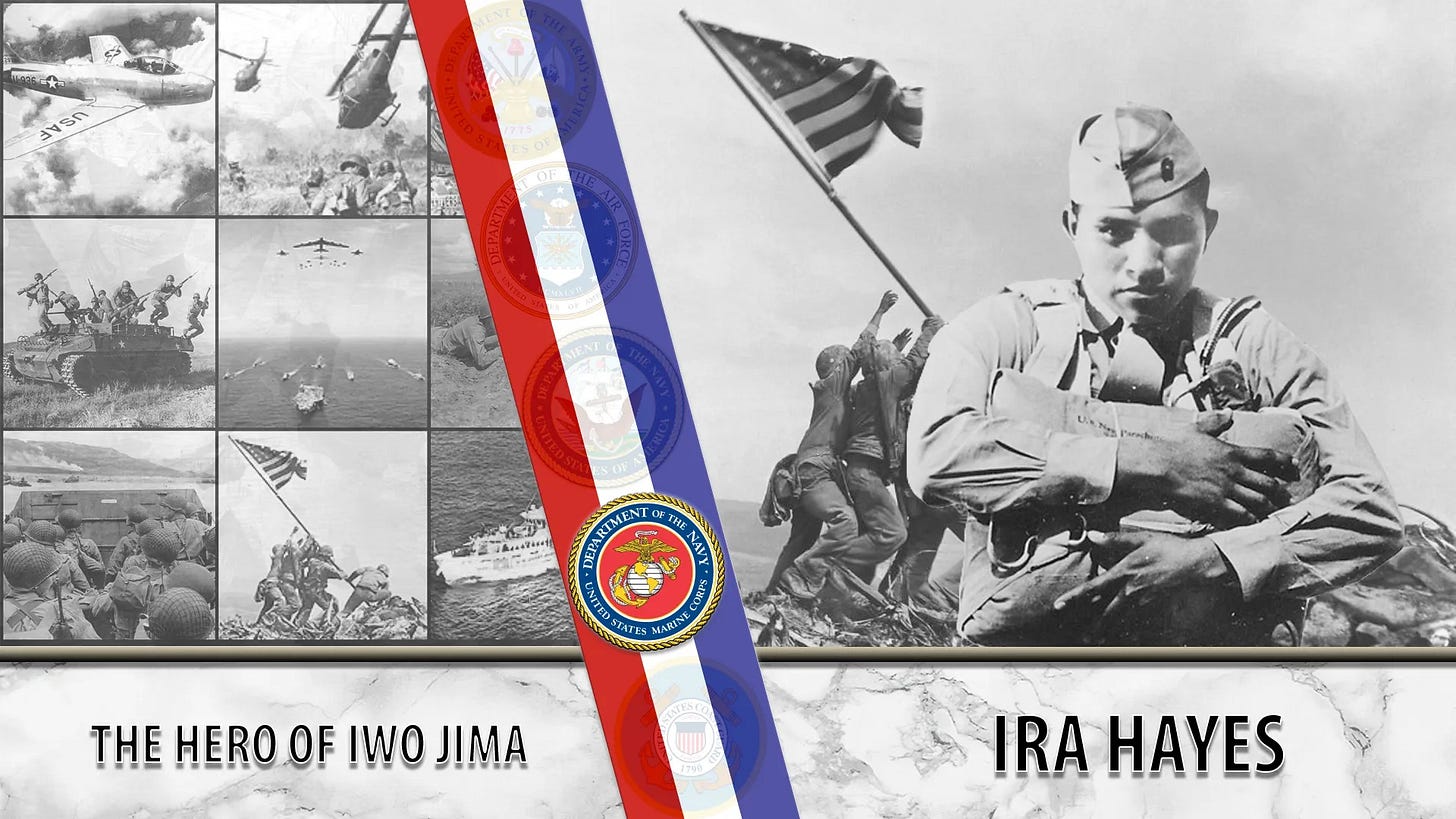

The man in black and the man under the flag—Johnny Cash and Ira Hayes are American legends framed by rugged truths. The story of Ira Hayes haunts me. What should’ve been the light of honor—raising the flag at Iwo Jima—became a burden of fame. On February 23, 1945, Ira Hayes helped to raise an American flag over Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima, an event photographed by Joe Rosenthal of the Associated Press. Hayes and the other five flag-raisers became national heroes because of Rosenthal's now-iconic photograph.

However, Hayes was never comfortable with his new-found fame, and had been heard to say he wished “that photographer had never taken that photo.” After his service in the Marine Corps, Hayes became an alcoholic. In January 1955, after a night of bingeing, he died of exposure to cold and alcohol poisoning. With full military honors, he was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Before and after his death, Hayes was commemorated in art and film. A giant Marine figure of Hayes raising the flag on Iwo Jima is included with the other five flag-raisers on the 1954 Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Virginia. In 1949, he portrayed himself raising the flag in the John Wayne movie, SANDS OF IWO JIMA. In 2006, Hayes was portrayed in the World War II movie FLAGS OF OUR FATHERS, directed by Clint Eastwood. In 1961, his life story was the subject of the movie, THE OUTSIDER, starring Tony Curtis as Hayes. This film inspired Peter LaFarge to write “Ballad of Ira Hayes.”

Hayes only wanted to do his duty as a soldier. Yet, the Armed Forces "publicity machine" coerced the shell-shocked Hayes to go on the road to (successfully) sell War Bonds and encourage war-weary Americans. Hayes was a Pima Indian from a humble background who found himself sharing the spotlight with President Truman, generals, and celebrities. However, becoming "a war hero" did little to combat the racism he faced. He drowned his traumas in drink. The horror and the hoopla were too much for the quiet patriot to bear.

There are others who’ve done comparatively less for war or peace, yet they get more "air time" in classrooms and pop culture than Hayes does now. Johnny Cash was my connection to Ira Hayes, if not to underdogs and reluctant heroes everywhere. Cash felt a special kinship with Hayes. Both men had served in the military to escape their lives of rural poverty. Both men longed for new opportunities. Plus, both suffered from addiction problems, Cash and his pills and Hayes with alcohol.

In 1964, Cash contacted Hayes’s mother and visited her and her family at the Pima reservation in Arizona. Hayes’s mother presented Cash with a gift, a smooth black translucent stone. The Pima call it an “Apache tear.”

The legend behind the opaque volcanic glass is rooted in the last U.S. cavalry attack on Native people, which took place on Apaches in the state of Arizona. After the slaughter, the soldiers refused to allow the Apache women to put the dead up on stilts, a sacred Apache tradition. According to legend, Apache women went into intense grief and shed tears for the first time ever, and the tears that fell to the earth turned black. Cash, moved by the gift, polished the stone and mounted it on a gold chain.

“Ballad of Ira Hayes” was later covered by several artists (including Bob Dylan and Kris Kristofferson), but, Cash had the final say. In July 1972, Cash was invited by President Richard Nixon to the White House. As media hordes huddled nearby, the country music superstar discussed prison reform with the self-declared leader of America’s “silent majority.”

“Johnny, would you be willing to play a few songs for us,” Nixon asked. “I like Merle Haggard’s “Okie From Muskogee” and Guy Drake’s “Welfare Cadillac.” The architect of the GOP’s Southern strategy was asking for two expressions of white working-class resentment.

“I don’t know those songs,” replied Cash, “but I got a few of my own I can play.” Dressed in his trademark black, his jet-black hair a little longer than usual, Cash strapped on his Martin guitar and played three songs, all decidedly to the left of “Okie From Muskogee.”With the nation still mired in Vietnam, Nixon listened with a frozen smile to Cash perform the explicitly antiwar “What is Truth” and “Man in Black” (“Each week we lose a hundred fine young men”). Nixon was about to sweep a re-election victory, but here was a confrontation with a president who was popular with Cash’s fans. It was a glimpse of how Cash saw himself — a foe of hypocrisy, an ally of the downtrodden. Of the three songs that Cash played for Nixon, the most enduring, and the truest to his vision, was “Ballad of Ira Hayes.”

Cash consistenly sang about the temporal and the eternal, intertwining the world views of a hardscrabble working man with that of a mystic. Throughout my life, in consistent and sometimes surprising appearances, Cash spoke to me about spiritual matters, even if I didn’t get it on the first pass. No matter where I went as a kid, the “boom-chicka-boom” of Johnny Cash and The Tennessee Three were playing in the background, with emphasis on the Sun sessions and the prison albums. Cash was one of the unifying soundstreams amongst family and friends who’d, otherwise, never agree on what to listen to.

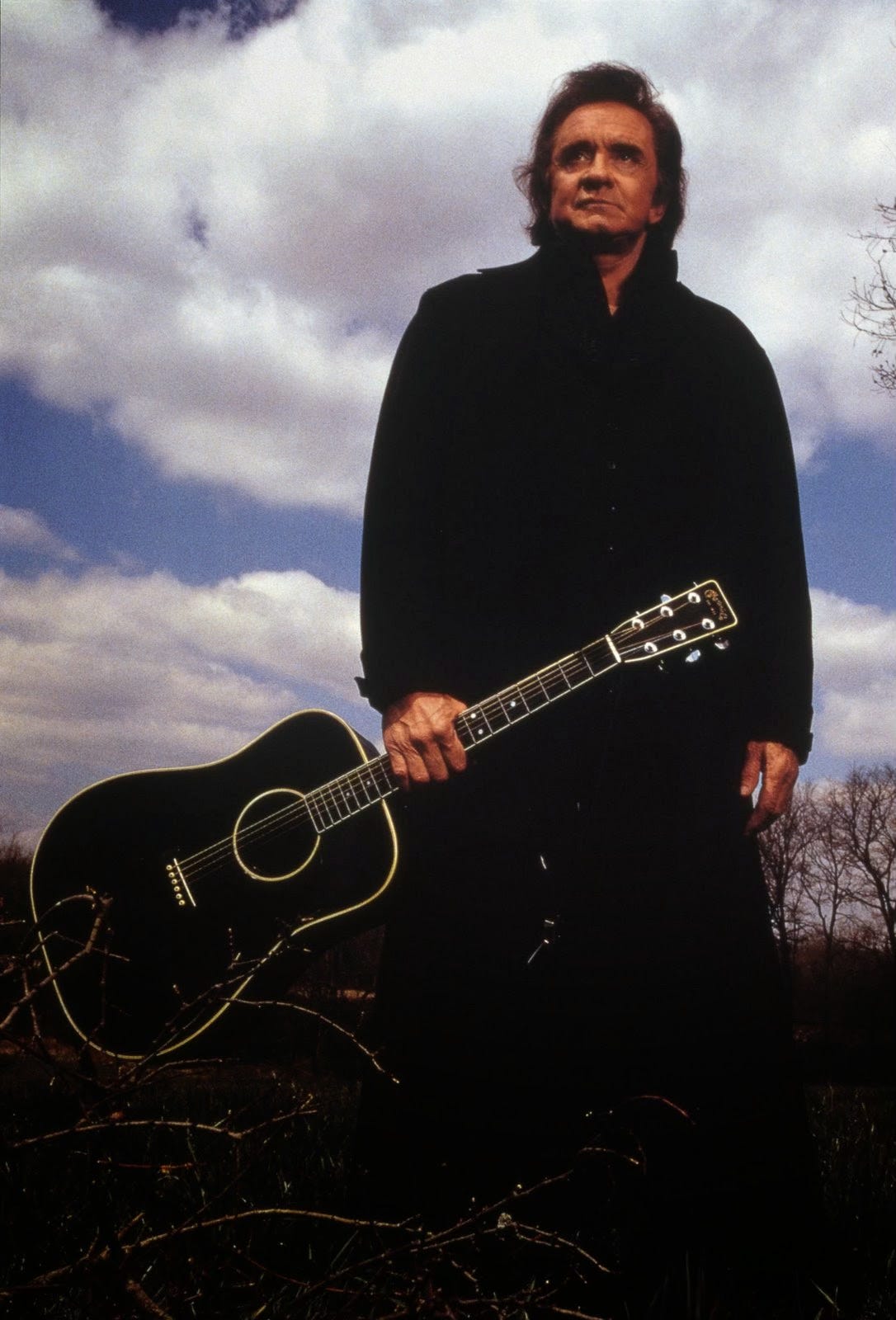

More than a singer-songwriter and recording artist, Cash was an Everyman and a Renaissance Man that communicated with almost everyone. As one of the towering influences of Twentieth Century popular music, his songs and sounds encompassed blues, folk, gospel, pop/rock, and rockabilly. From his early days as a rockabilly-channeller and star of The Sun Sound of the 1950s, to his decades as an international representative of country music, to his resurgence to fame in the 1990s as a living legend and an alternative country figurehead, Cash inspired countless artists. Upon his death, Cash was revered by the greatest musicians of his time. His rebellious image and “Man in Black” stance resonated with punk rockers. Paradoxically, his somber and humble demeanor endeared him to rebels and conformists alike.

Hearing “Ring of Fire” on my Dad’s car AM radio is one of my earliest memories of being affected by music. On occasion, in my live set, I perform a punkabilly take on “Ring of Fire.”

The Cash persona influenced me as a performer and stylist. Maybe that’s why I’m fond of black. Guitar is not my main instrument, but Cash’s rudimentary, pan-rockabilly percussive technique made me want to explore the guitar as a tool for getting things done, like when I wrote “Desert Ruby,” “Throw the First Stone,” and other songs.

A troubled but devout Christian, Cash has been characterized as a "lens through which to view American contradictions and challenges.” He was a Bible scholar who wrote a Christian novel, MAN IN WHITE, an historic novelization on life of the Apostle Paul. Cash also made a spoken word recording of the entire New King James Version of the New Testament. Even so, Cash declared that he was "the biggest sinner of them all,” and viewed himself as a complicated and contradictory man. He is said to have "contained multitudes," and has been deemed "the philosopher-prince of American country music.”

Long after BITTER TEARS and winning his fight with drugs, his support for the Native cause remained unchanged. He went on to perform benefit shows on reservations — including the Sioux reservation at Wounded Knee in 1968, five years before the armed standoff there between the FBI and the American Indian Movement (AIM)— to help raise money for schools, hospitals, and other critical resources denied by the government.

In 1980, Cash told a reporter: “We went to Wounded Knee before Wounded Knee II (the 1973 standoff) to do a show to raise money to build a school on the Rosebud Indian Reservation, and to do a movie for the Public Broadcasting System, called TRAIL OF TEARS.” He joined Kris Kristofferson, Willie Nelson, and Robbie Robertson to call for the release of jailed AIM leader Leonard Peltier.

Kristofferson summed up the spirit behind Cash’s protest album in his eulogy for Cash, who died in 2003. Cash, he said, was a “holy terror … a dark and dangerous force of nature that also stood for mercy and justice for his fellow human beings.”

Four years before his famous concert at Folsom Prison, four years before AIM formed, and at the pinnacle of his commercial success, Cash insisted on producing an uncommercial, deeply personal protest record that was a close as he could come to truth. He would always cherish it. “I’m still particularly proud of BITTER TEARS,” Cash would say near the end of his life.

When I listen to and sing along with “Ballad of Ira Hayes,” I feel a harsh sting of sorrow, but a clear promise of wisdom.

POSTLUDE: This article was updated in 2024, in time for Native American History Month in November, but I actually started writing about this in 2007. Two years later, author Antonino D’Ambrosio issued the book, A HEARTBEAT AND A GUITAR: JOHNNY CASH AND THE MAKING OF BITTER TEARS.His research expanded upon the depth of Cash’s feud with the music industry and the subtext of his activism for Native Americans. I am indebted to D’Ambrosio’s writing as I update this article in 2014. In 2016, PBS issued an excellent documentary about BITTER TEARS and the controversies surrounding it:

#johnnycash #irahayes #bittertears #peterlafarge #navajo #pima #johnnyjblair #laughingboy #kriskristofferson #woundedknee #richardnixon #leonardpeltier