Playing What I Don’t Hear: What I Learned from Miles Davis

Birthday Salute to the Byronic Dark Prince, born today in 1926

"Miles Davis is a sound…the whole earth singing!"—Chico Hamilton.

When one is thirteen years old, everything is extreme; nothing is neutral. Emotions, hormones, and questions are exploding all over the place. In the midst of that crossfire, between the formation of an adult mind while still having the soul of a kid, one is supposed to get a grip on persona. Maybe one embraces music that affirms one’s identity, moods, and thoughts. Music becomes a loyal friend; a sonic protection; a filter; a way to translate the world and feel connected to something larger and eternal.

In the blush of adolescence, when I was thirteen, my early 1970s music library was a receptacle of records that friends had jettisoned. They said the music was "crap/too weird.” I gladly took in the orphans, acquiring (for free, trade, or soda money) copies of the first two King Crimson albums and Miles Davis’s BITCHES BREW.

Those LPs pillared my then-obsession with art-rock, jazz, and progressive music. The music that was "crap/too weird" changed my life and is still reaching new listeners years later, outlasting and enduring.

Even though they came from different countries and time-frames, both King Crimson and Miles Davis conversed in future-primitivism, boundary-bending dynamics, and tactful sophistication. One musical idea would have meta-layers of quiet, calm, and romantic mysticism, played at the rhythm of a sea turtle. Next would be an atom-splitting irruption of outrageous chord patterns, exospheric harmonies, and fiercely passionate virtuosity.

Loving this music didn’t do much for me socially. Family and friends could relate to Janis Joplin and Neil Young (as could I), but playing side one of King Crimson’s ISLANDS guaranteed that someone would grab for the tone arm while crying, "Why are you listening to this awful music!?!" The usual breaking point was the ghostly, wordless vocal improvisation by soprano Paulina Lucas during Formentara Lady, a long piece that was (conveniently) influenced by Miles Davis’s contemplative masterwork, In a Silent Way.

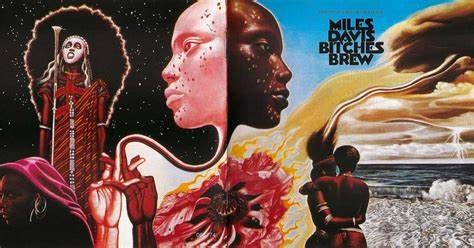

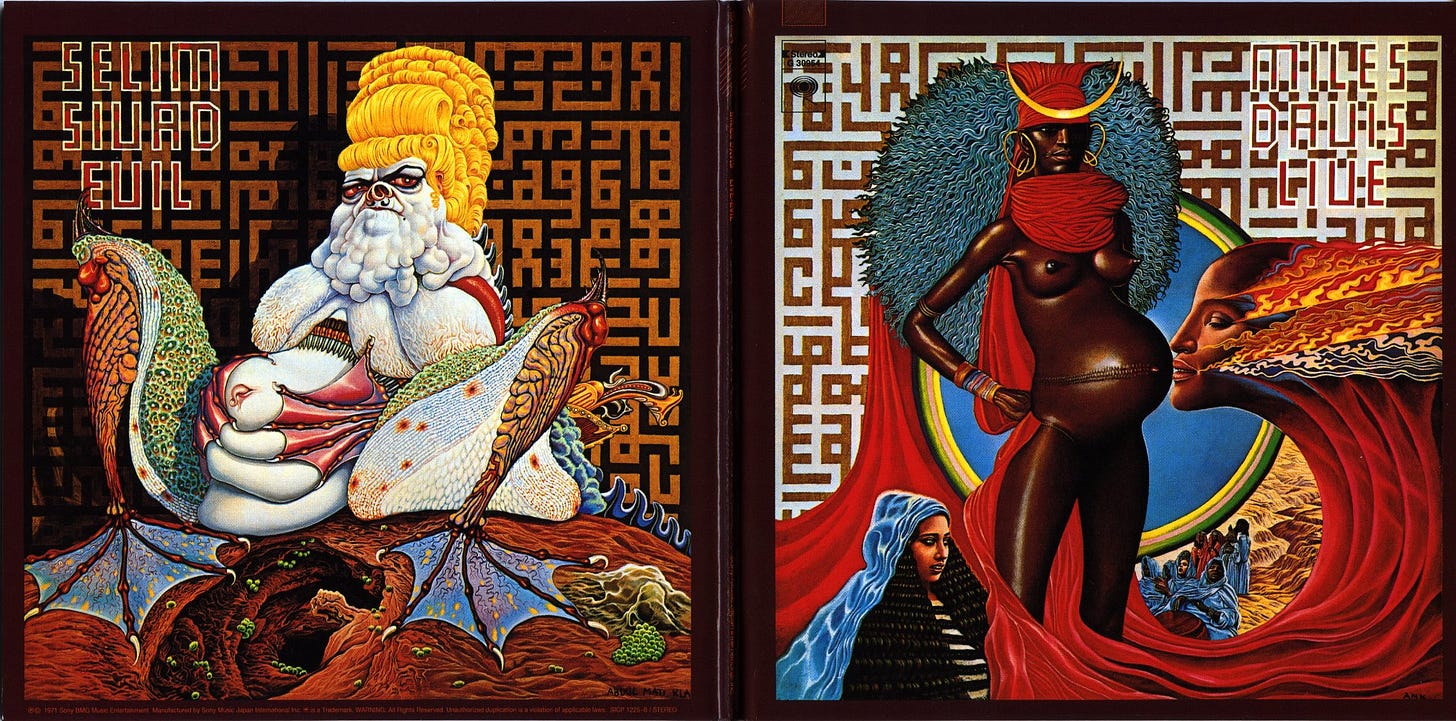

What I Say comes from LIVE-EVIL, a 1971 double-set said to be an extension of BITCHES BREW (1969). The cover art on both albums were by Mati Klarwein, the Isreali surrealist who’d studied under Salvador Dali. Klarwein’s other clients included Jimi Hendrix and Santana.

Davis guided the exotic cover art images on both projects. "I was doing the picture of the pregnant woman for the cover," said Klarwein, "…when Miles called up and said, ‘I want a picture of life on one side and evil on the other.’" Davis elaborated in his autobiography, "…Reversal was the concept of the album…with those two paintings on the front and back. One gets into love and birth, and the other into evil and the feeling of death."

Birth, love, community, and identity express the blessing of life on the front. The back cover shows a squatting toad-parasite creature, nightmarishly pale with jaundiced eyes.

Like badges of honor, I took these albums to high school to share the music with my friends. The implied Afro-centrism in Klarwein’s art, combined with Davis’ ongoing advocacy of ethnic pride, seemed timed as a cocktail for the Black Power Movement of the 60s. There is regular criticism that Davis was a racist white-hater, but this is grossly ill-informed—if just on the count that he befriended and championed countless white colleagues over the years (not to mention that Klarwein’s art is an abstract tract for racial unity).

Davis came from a financially stable, hard-working, and well-educated family. His father told him, "There is no excuse for being poor." It was also a time when Black Americans were spurning the "bowing and scraping" stereotypes perpetuated by the entertainment world. By the 1940s, artists like Davis, Dizzy Gillespie (who reinvented the world "cool" for our cultural vernacular), and others not only bucked the system, but made their own

(In photo L-R Tommy Potter, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Max Roach in 1957).

Fast forward to the late Sixties race riots and the death of Martin Luther King, Jr. When James Brown sang Say it Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud in 1968, it was misconstrued as a war cry against whites. In truth, Brown was only telling his brethren to stop complaining and do something useful with their lives. What else should we expect from Brown, who wrote songs like Don’t Be a Drop-Out and single-handedly stopped race riots that year?

As for Davis, his family taught him to never, ever tolerate intellectual laziness and prejudice (both tend to work together). When Davis said The Grammy Awards should be "The Mammy Awards," or made cracks about showbiz and society, it wasn’t about skin color. It was about not accepting mediocrity in any form, from anybody, anytime.

Duke Ellington called Davis the "Picasso of jazz." Both Davis and Ellington share the same space as David Bowie, Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan, Franz Liszt, and Igor Stravinsky in that each experienced prolific lives that wind back to a spiritual center of shape-shifting endurance. Every time someone said “they’re washed up” or "they burned out," these artists rose back like a Phoenix. To be constantly shifting stylistic gears, these artists confounded, even angered, their allies and as well as their critics. Yet, all of these artists sustained careers and imprinted our culture. Davis taught me to never give up and keep it fresh.

Then there was the art of squeezing lava out of musicians. Davis said, "I tell my musicians to be ready to play what you know and above what you know. Anything might happen above what you’ve been used to playing."

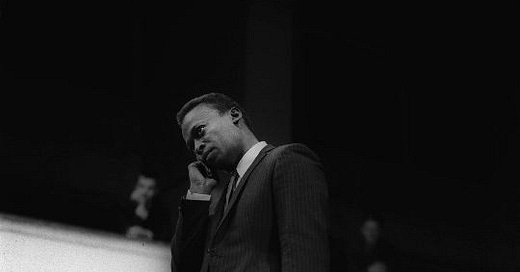

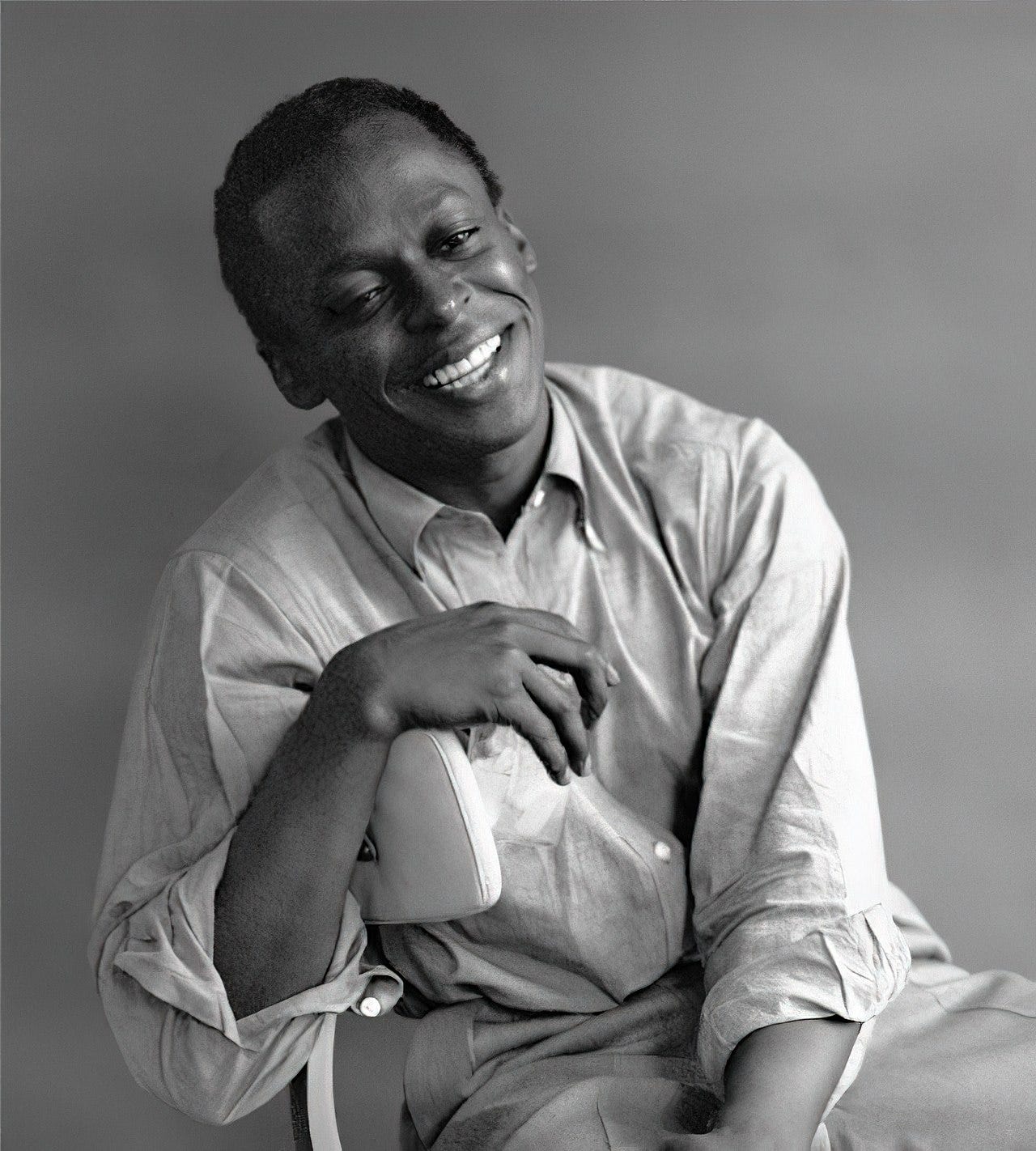

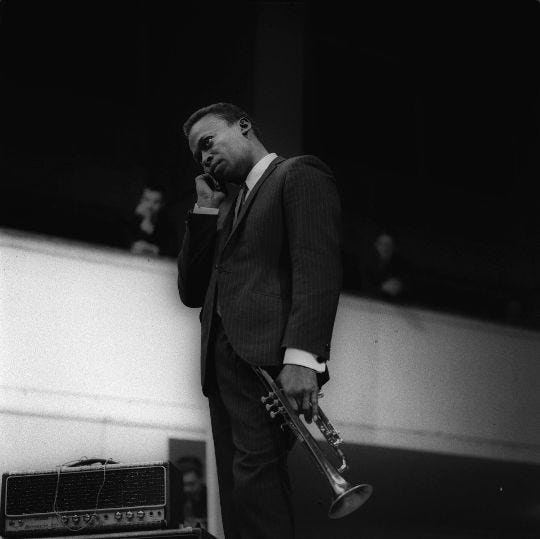

Davis’ career started in the 1940s, gigging for steady pay by age 16. He was an early voice in be-bop jazz, zig-zagging between formal education at The Julliard School of Music and street-level mentoring from the iconoclastic Charlie Parker. By the mid-50s Davis was confirmed as a trumpet giant, bandleader, arranger and innovator, promoted as a Byronic black man, or The Dark Prince.

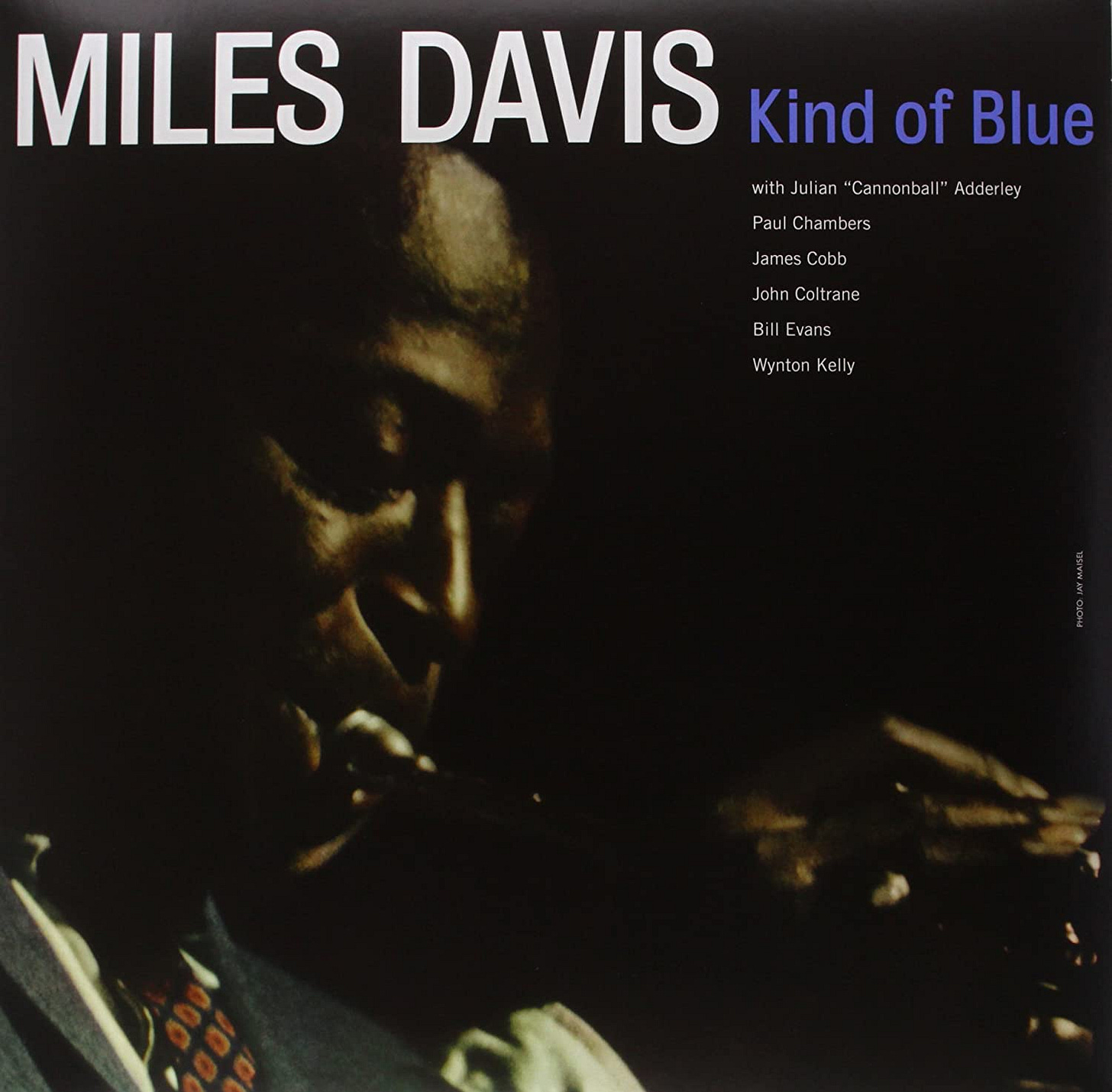

In 1959 he released the jazz touchstone, KIND OF BLUE, perhaps the single-most influential and best-selling jazz album of all time. A year later he released SKETCHES OF SPAIN, a hybrid of classical-jazz in the shadow of Duke Ellington (no serious music library is without SKETCHES).

By the 1960s, David had perfected an economy of technique, defined as "figuring out what notes I don’t have to play." It wasn’t about restraint. It was about experience, intensity, and letting the music breathe. He told his musicians to "play what you don’t hear," riffing on Thelonious Monk’s order to make the other musicians sound good when you’re in a group. Musicians came and went, but Davis had no problem finding titans to join his bands, which included Cannonball Adderley, Ron Carter, John Coltrane, Bill Evans, and other now-legends of jazz.

Davis learned to communicate almost wordlessly with band members (a "telekinesis" he learned from Parker). Davis gave new meaning to the phrase "uncharted territory" as charts were used sparingly, if at all. Instructions to musicians could be totally non-musical; Brazilian percussionist Airto Moriera was told, "Don’t play the rhythm. Play colors. Tease."

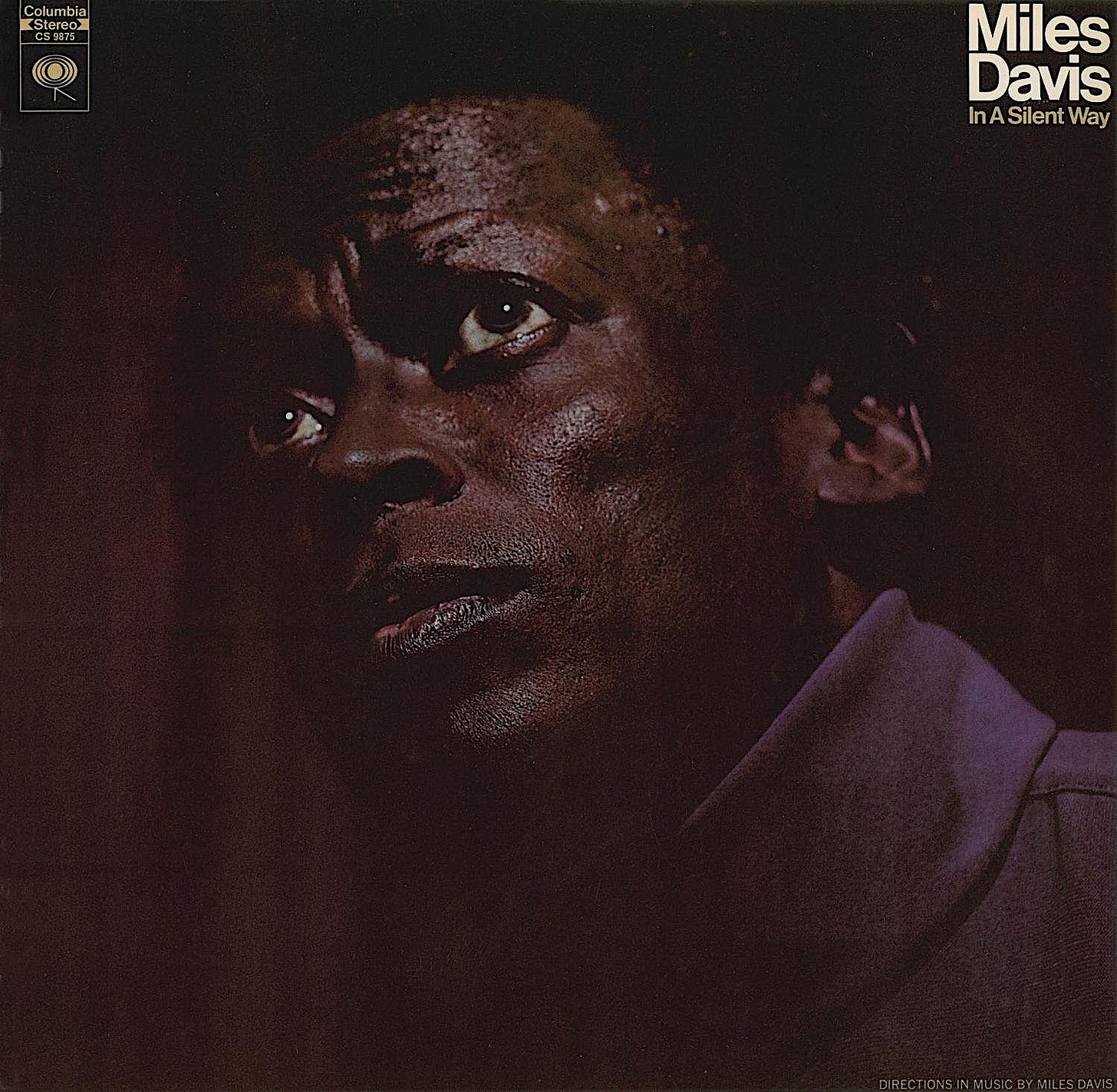

By 1967-8, Davis was well into an electric aura. Modalism became his main method. A set would flow freely and unbroken. Some called it "free-bop." His marathon recording sessions were edited into different albums, as it was with the watershed IN A SILENT WAY sessions. He also started to employ the "studio as an instrument," using editing, effects, and remixes to create compositional pastiches.

One indication of Davis’s new direction was his cover of David Crosby’s Guinevere. People visiting Davis’s apartment noticed his record collection was stocked with The Beatles, James Brown, The Byrds, electronic music, The Fifth Dimension, Indian music, showtunes, Sly & the Family Stone, and Karlheinz Stockhausen. Davis met with Jack Bruce, Paul Buckmaster, and Jimi Hendrix to discuss collaboration.

1968 set off one of the most divisive and controversial periods in jazz. The music Davis made between 1968-75 has been both celebrated and reviled. For me, it is a body of work that never ceases to fascinate and nourish.

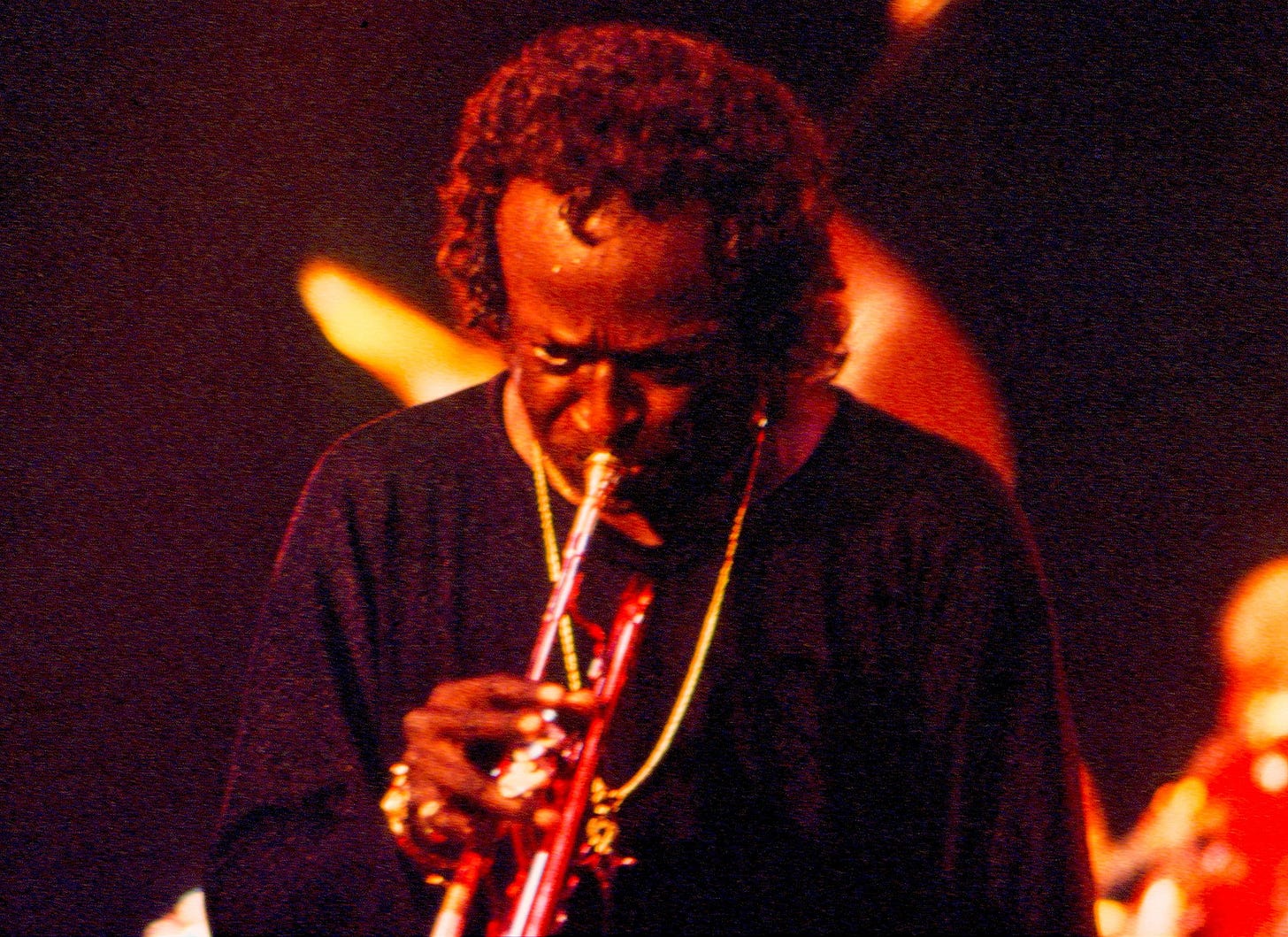

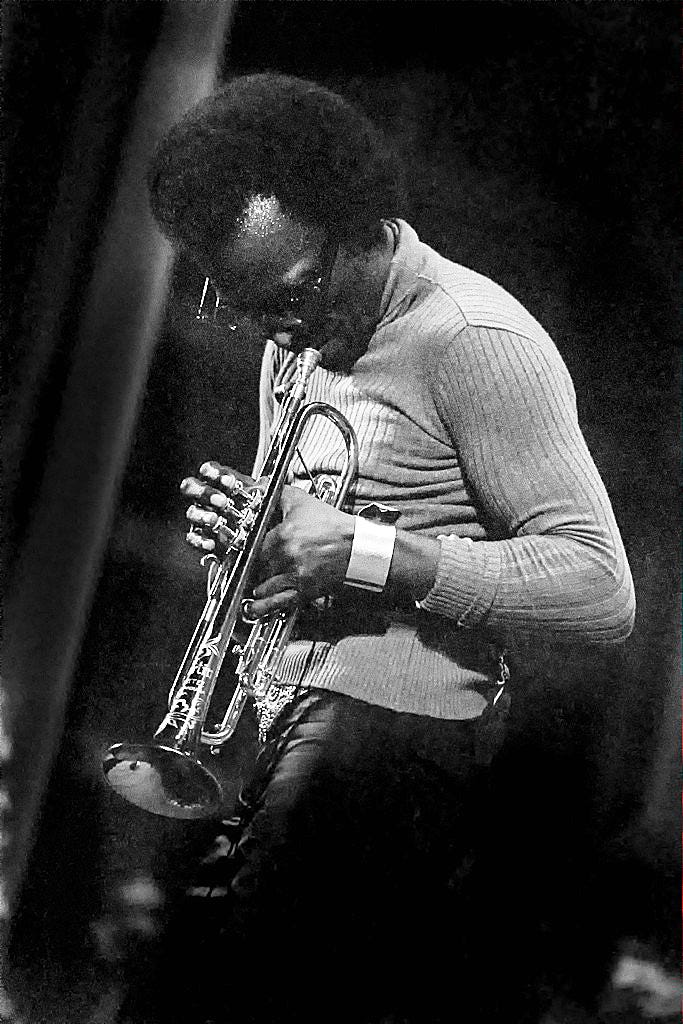

Like Dylan, Davis was hounded for "going electric." He began to treat his trumpet with echoplexes and a wah-wah pedal. Traditional jazz was being skinned alive and boiled in a cauldron of aggressive African and Latin spice, James Brown-influenced hard funk, and acid rock, signified by the cranked electric guitar of a hot new Irish guitarist named John McLaughlin.

The result was BITCHES BREW, a landmark double-album that forever, and instantly, changed the course of jazz.

The music was dubbed fusion jazz (or jazz-rock fusion), and Davis’s core group—Billy Cobham, Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, Dave Holland, John McLaughlin, Wayne Shorter, Tony Williams, Joe Zawinul—would branch off into their own fruitful entities: The Headhunters, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Return to Forever, Weather Report, Tony Williams’s Lifetime (with Allan Holdsworth), etcetera. Fusion infuriated the old guard ("I thought Miles Davis was dead…" Charles Mingus, 1971) but they were barking at a hurricane.

The jazz world branded it as heresy, but BREW roused the music world. It was celebrated by everyone from Henry Mancini to producer/ambient music pioneer Brian Eno, who said, "He did something that was extremely modern; something you can only do on records…he took the performance to pieces, spatially. Now, those things were done by a group of musicians in a room, all sitting close to one another…but they were close-miked, which meant that their sounds were quite separate from one another. When Teo Macero (long-time Davis producer) mixed the record, he put them miles apart…the impression you have is that you’re on a huge plateau…all of these things are going on…almost on the horizon…."

Davis realized that LIVE-EVIL had its own purpose; a cerebral, earthy power separate from BREW. "I was learning how to play my trumpet over all of this electrical sound, and that was a real eye-opener…on this album I was hearing things up in the upper register. On What I Say I played a lot of high notes on trumpet, notes I usually don’t play because I don’t hear them, but I heard them a lot after I started playing this new music."

On LIVE-EVIL, dreamy, unhurried studio takes were paired with Herculean concert recordings culled from four nights at The Cellar Door (Washington D.C.) in December 1970 (all now released in a box set). At 21:30 minutes, What I Say is one of the unedited live cuts. That night, few ensembles in history played with the stamina of this group.

What I Say is kicked off by drummer Jack DeJohnette, whose kit "sounds like jazz" but plays with a funk/rock muscle as if Ginger Baker, Buddy Miles, and Clyde Stubblefield were all one man. Davis said, "I gave Jack this drum rhythm …I wanted him to lock everything in with that figure, but I wanted it to have some fire. For me, that piece sets up the album…"

Next comes the relentless bass work of (then 19-year old) Michael Henderson, whose previous gigs were with Aretha Franklin and Stevie Wonder. Henderson was a player of "superb feeling and rhythmic drive." His flair for producing hypnotically simple grooves gave the band a foundation. Davis said, "He’s incredible. He can play bass lines when there’s nothing there but air." Henderson’s overdriven tone hinted at acid rock, but the funky, buoyant Bb notation came from sweaty worship in the Sanctified Church.

Jarrett (on two keyboards) picks up the momentum with a two subtext melodies. In the lower registers, he sounds like a construction worker building a skyscraper, singing a manly song while setting up another rivet. In the upper registers, Jarrett plays like a skat-singing kid on a sunny day.

After a fast-moving chromatic bass/keyboard crescendo, Davis hits hard with three headlight-flashing notes—the main theme of What I Say. He mimics taxi horns and sirens before easing down to a velvety melody that dances on augmented fourths. He flips to bright, joyful major scales (like Hugh Masakela on speed) before madly swinging back to horn-replications of couples talking loud, dogs barking in the park, and kids running in the street. Davis biographer/trumpeter Ian Carr said Davis hit "notes so high they were approaching bat frequencies. Everything is taken to its ultimate extremity: the sheer physical range of the trumpet; the speed of the phrases; the intensity of the rhythm…"

Gary Bartz picks up the conversation on soprano sax, with a soulful, dexterous coherency that would fly in both a James Brown workout or a space jam. Next is John McLaughlin, whose revved-up guitar approaches the traffic in an 8-cylinder eastern scale, then cools down in a classically-informed hard rock fashion.

Next comes one of the most exhilarating solos in Jarrett’s career. His distorted Fender Rhodes alternates with smoky organ, creating amazing runs that quote Bach, Stravinsky, and Art Tatum at dazzling turns. This segues into DeJohnette’s drum solo. Many people (including drummers I know) think drum solos are pointless. Yet, even non-fans of the drum solo hear this and say, "That drummer is levitating, even increasing in energy." What’s more incredible is that he’s been playing this ferociously for fifteen minutes!

Throughout, Airto "teases and colors" with cuica, rattles, whistles, and donkey jaw. A Tinkerbell-like fife/flute player (probably Bartz, uncredited) follows and flits under the guitar and keyboard solos.

The main theme is reprised by Davis. Suddenly, at 20:00, What I Say flips to a rubato cool-down. Davis plays long notes while Jarrett winds down with miniaturized baroque percolations. Airto submits a half-time cabassa pattern. It’s like finishing a jog through a vibrant city. Your body wants to chill but your brain is still racing and your heart is happy.

What I Say is a piece that forever set the bar for how I perform. Once you’re on a stage or running a recording, you need to perform like it’s a matter of life and death. You have to play what you don’t hear.

#milesdavis #liveevil #jazz #birthday #airto #michaelhenderson #johnmclaughlin #jackdejohnette #keithjarrett #fusionjazz #trumpet #johnnyjblair #bebop