7/17/22

I AM A SURREALIST SONGWRITER

Songwriting can be defined as a successful combination of melody, harmony, and rhythm, but that would be a gross oversimplification. like comparing it to algorithms and formulas. Songwriting is also a communication skill that involves disciplines both mysterious and explicit. Writing a song is an art that connects people with the mind, body, and heart, emotionally, socially, and even neurologically and spiritually.

In today’s culture we’re used to songwriters who make their summations in around 4 minutes or less, and in my experience, contemporary songwriters fall into four camps:

1. The hit-makers, guided by marketing and packaged in state-of-the-art production, going for the biggest possible mass appeal. They use simple melodies and rhythms with melodic “hooks” telling tales with scenarios about people, places, and things. Nearly every song has a simple topic, romantic hypothesis, a rah-rah chant, or a story from sad to happy to shocking to silly with a “beginning to end” formula.

2. Confessional songwriters use similar tactics but aren’t going for formulaic hits or a “pop jugular.” The confessionals express from the heart in the full range of the human experience, perhaps as an extension of the medieval bards and Old Testament psalmists. Their audience wants melodies and rhythm but also expects mindful lyrics and wordplay. The confessionals are poets who are also musicians. This group makes a personal connection to a song without much pause for marketing concerns and production.

3. Commissioned songwriters hired to write for musicals and operas with precise themes, or songs written for events, specific audiences (children, ethnic groups), religious themes, social and/or political outcry.

4. Rappers narrating with a raw force driven by electronics and rhythm—arguably an extension of the African griots (village storytellers).

Some songwriters create their own brand with their own vocabulary—Bob Dylan springs to mind. Others put the schools together and rebuild them—I’m thinking Lennon/McCartney. However, many song-pluggers stay with one brand, one school. I’m familiar with songwriter groups with rules about lyric word-choices and how to structure melody, harmony, and rhythm—the 3 elements of all music (MHR). For them the end game is excellence in fine song-craft. However, the problem I see is that once one aligns oneself with a style one might have to stick with that one brand. Otherwise, people get confused, and the big music companies don’t tolerate flops or surprises.

I am an independent artist who has publicly released at least 200 original songs (not counting instrumentals and other compositions). I’ve been told that if I want to be more successful, I should pare down, trying “going country” or write more blues or pop or even kid’s music, but hearing these well-meant suggestions makes me feel shoe-horned. I already work in mainstream styles (all kinds of pop/rock) and have written hooky topical songs like “I Wanna Bein Pennsylvania”

and “If I Could Dress Like Clive Owen”

—two songs that came to me in what I call “a Cole Porter moment,” when a phrase glues itself to a catchy melody and I just finish it off.

Then one day I realized that songwriting itself is just a part of my continuum in entertainment and edification. My over-arching desire is to give people quality experiences with concerts, recordings, and engagement—which includes instrumentals, sound collages, humor, and “theatre of the mind” that reaches people on another level. I’m not interested in being yet another white dude singer-songwriter with an acoustic guitar on a stage saying, “This next song is about...” That’s not my job or calling. So how and why did I compose and record over 200 original songs and get them out there?

Some of my songs came “free delivery,” ready-made drop-shipped straight from God while I was doing something else. Other songs emerge fully formed in my dreams. Brian Wilson and Neil Young say they have dream-songs and I know it happens to other songwriters. Since surrealism relates to dreams, I know I’m not alone.

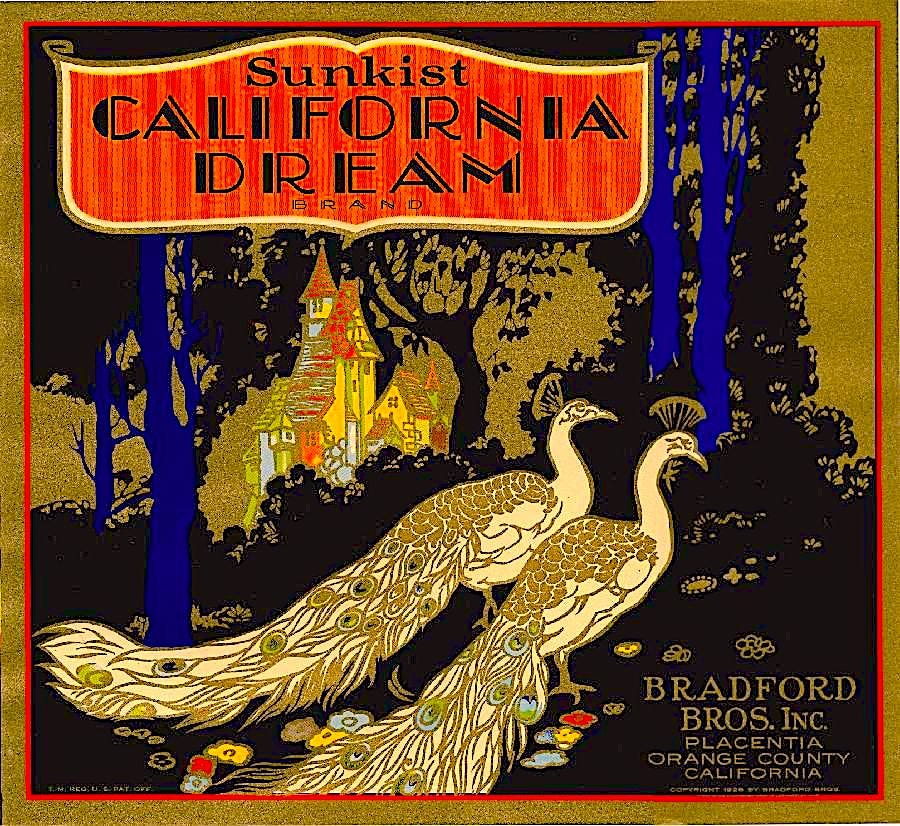

My song “Desert Ruby” is my metaphysical allegory for how I describe Los Angeles and Southern California. The lyrics are a hybrid inspired by orange crate art, satellite photography, and real-life characters merged dream sequences I had during a bus ride. It’s a catchy song but the words are wide open to interpretation, and all the interpretations work. The hazard of the dream-song is catching it before it evaporates from the brain (Keith Richards solved that by keeping a recorder next to his bed—that’s how “Satisfaction” came to be).

Sometimes I use the Donald Fagen method, which is to take words that sound good in my mouth and wrap them into a melody—let the words take on meaning later—the case when I wrote “Night Garden.”

This uses words as impressions, like in dreams. The rest of the time, however, I create songs the usual way, sitting with an instrument and sculpting it out, but, honestly, I’m not at all motivated to work like that. I’ve been writing songs since age 12 and the more I got into it the more it seemed that me not fitting into a “songwriting school” was a deficiency on my part, even making me feel stupid. That’s the sin of comparing myself to others. Then I made a discovery!

I’ve always enjoyed the study of non-musical disciplines such as filmmaking, painting, photography and writing and how that resonates with music-making. Joni Mitchell, one of the most influential and remarkable songwriters in history, had little musical training. She approached songwriting the same way she approached her paintings (she even made her own album covers). Recently I read about 20th Century surrealists and their explanations for how and why they came up with such challenging works that somehow reached many people and had a massive impact on visual arts, films, literature, and music. As I read more about surrealism, I had a “Eureka moment.” I realized they approached their art the same way I approach songwriting!

The 20th Century surrealists were an eccentric group, with colorful figures such as Salvador Dalí, who said, “Surrealism is destructive, but it destroys only what it considers to be shackles limiting our vision.” Dali’s 1931 painting “The Persistence of Memory” is one of the most recognized examples of surrealism, with its sparse landscape and melting clocks. Images like these have inspired my songs, as have the abstract plays of Charles Williams and the poetry of T.S. Eliot. Surrealist artists, often influenced by dreams, sought to reveal the strangeness they saw flowing beneath everyday life. French writer André Breton (arguably the leader of surrealism), said the primary aim of surrealism was “to resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super-reality.”

René Magritte was a Belgian surrealist painter who influenced pop art and minimalism. He’s best known for painting men in bowler hats. Like other surrealists he had a fondness for putting ordinary objects in a bizarre context, saying, “If the dream is a translation of waking life, waking life is also a translation of the dream.” This recalls the importance of dreams in antiquity, when kings would hire prophets like Daniel to interpret dreams.

“It’s the artists who do the dreaming for society,” said Méret Oppenheim, who rose to fame in 1936 with an exhibition of everyday objects arranged in surrealist fashion. Her most famous piece, “Object,” consists of a teacup, saucer, and spoon covered with fur from a Chinese gazelle. Similarly, American visual artist Man Ray said, “I do not photograph nature. I photograph my visions.” He saw himself as a painter, but he is more famous for his experimental photography using “camera-less” techniques. His goal was to “make my photography automatic—to use my camera as I would a typewriter.”

The Donald Fagen songwriting method echoes surrealist painter Joan Miró, who said, “The painting rises from the brushstrokes as a poem rises from the words. The meaning comes later.”

Artist Jean Arp transitioned from dadaism and surrealism before founding the “Abstraction-Création” movement in Paris. Best known for his biomorphic sculptures, he said, “We do not wish to copy nature. We do not want to reproduce—we want to produce...as a plant produces a fruit and does not itself reproduce.” Songwriters can adapt that to mean that even though we re-use chord patterns and scales to create our songs, each song is one of a kind.

German painter Max Ernst was a pioneer in both dada and surrealist movements. His traumatic experiences as a soldier in World War I made him see the modern world as irrational, which reflected in his paintings, sculptures, and poems. He said, “Painting is not for me either decorative amusement, or the plastic invention of felt reality; it must be every time: Invention, discover, revelation.”

After reading these quotes and studying the work of these artists, I felt a kindred spirit. If I take out the words “painting” and replace that with the word “music,” I arrive at the same place. I am a surrealist songwriter.

Does this make me more prolific or lead me to a hit song? We shall see. What I do know is that I’m not under any obligation to be marketed as something I’m not. My obligation as a songwriter is to fulfill my God-given purpose, whether it’s something abstract or goes for a pop music jugular. My message to other songwriters is to find the path that suits you best. One can learn a lot by studying the disciplines of hit-makers and confessional singer-songwriter, but ultimately, it’s between you, God, and your instrument. My job, my purpose, is to paint the air with music. What comes after is between you and the divine.

Article © 2022 by Johnny J. Blair

#surrealism #surrealist #songwriting #songwriter #singer #johnnyjblair #salvadordali #maxernst #jeanarp #donaldfagen #meretoppenheim #renemagritte #beatles #desertruby #nightgarden #mikegarson #cliveowen