It’s Diana Ross’s birthday. The following is an excerpt from my book, TIME TRAVELS ON A TURNTABLE (12 PIECES OF MUSIC THAT CHANGED MY LIFE):

The Supremes I HEAR A SYMPHONY: Fighting for Joy

Music is more than notes on a page and sounds in the air. Music can be the sword and shield against the ugliness of life. Music is a way to decipher, then transmit, those eternal values and a life larger than your own.

Diana Ross grasped these concepts when she was a teenager. A child of a church-going, hard working, and properly fed-and-clothed family, Ross was reared in a vector of middle-class dignity.

Ross had a cousin named Virginia Ruth, a talented singer and church choir director. Cousin Diane (later Diana) saw in Cousin Virginia a role model of artistry and refinement. She gave young Diane a feeling that music would elevate people and bring them closer to God. In 1955, Ruth was found dead on a road-side in Mississippi. There was no sign of an accident. It was not far from the site where Emmett Till was murdered. It was rumored that Ruth was killed by the Ku Klux Klan.

A year later, while attending high school in Detroit, a boy gave Ross a hard punch in the face and called her the n-word. She ran home and told her usually subdued mother about the unprovoked attack. Her mother loudly told her daughter to never let it happen again, and to fight back. Ross made a decision. Singing and music would be her sword and shield. She would join Florence Ballard and Mary Wilson to become The Supremes, a vocal group in an enormously successful creative engine that changed American culture and reached around the world: Motown.

1958 was the beginning of “the Motown sound.” Berry Gordy, followed by Smokey Robinson and others, made a decision: To be prosperous, they would dismantle racial barriers through a subtle assimilation of all music styles. Motown was not only commercial art—it was artistic subterfuge through the channels of AM radio and the three-minute pop song. Motown was christened “The Sound of Young America,” and that meant all America: red, yellow, black and white. Motown music was bought, danced to, and sung by the young, old, rich, poor, long-haired, short-haired, Democrat, Republican, religious, irreligious, redneck, and revolutionary. Motown was a universal celebration in a world gone mad.

The single I Hear a Symphony, released October 1965, was The Supremes’ sixth Number One hit. It came out during a string of sixteen commercial releases in less than twenty-four months--including a collection of British Invasion pop/rock covers, a country project, an album of jazz standards and show tunes, holiday-themed releases, and a tribute to the recently-departed Sam Cooke (another of my favorites; Cooke had a similar business template to Gordy).

“A tender melody, pulling me closer…”

I Hear a Symphony opens with the tautness of a suspended chord. The tension is quickly loosened by a soothing cascade of baroque couplets not unlike Handel or Vivaldi, said with dreamy vibraphone and a gentle jazz rhythm section. The music bristles with intimacy before Ross even opens her mouth to sing, “You’ve given me a true love, and everyday I thank you love, for a feeling that’s so new, so inviting, so exciting…” The melody balances on a chord sequence that reverences Bach’s joyful Air in G (a piece that informs many Motown songs).

Then Ross sings, “…Whenever you’re near I hear a symphony.” Shimmering strings trill back in vibrato, making the emotional thrill seem so literal. Benny Benjamin’s trademark drums kick up the masculine side while the deceptively simple feminine choruses of “baby baby/oooh symphony” give solid counterpoint behind a constantly-modulating melody (that a twenty-two-year old Ross worked very hard to keep up with).

In the spirit of Song of Solomon, musical terms and lyrics of Symphony are allegories on the wonders of a lover. The song is a union of vocal exuberance, romantic idyll, and creative ingenuity.

Symphony was written by the team of Holland-Dozier-Holland (H-D-H): Brian Holland, his brother Eddie, and Lamont Dozier. They’d been writing since they were teenagers and went on to make hit after hit for The Four Tops, Marvin Gaye, Martha Reeves, and many more. Besides being brilliant and prolific, H-D-H were musically well-trained. Gordy, a taskmaster, expected that all of his artists knew basic music theory.

Dozier later said, “We were keeping up not only with what was going on at Motown, but in the world, meaning The Beatles, The Beach Boys…There was definitely a standard…Everything that came out had a signature as well as it had to sound like a hit.” H-D-H, like Gordy, believed in thinking “outside of the box.” Dozier said they’d regularly go to chamber, opera, and symphony concerts “for song concepts.” Baroque, electronic, ethnic, and orchestral ideas and instruments became part of “the Motown sound.”

Early Motown hits like Money, Please Mr. Postman, and Mickey’s Monkey sold mostly to teens and were rooted in “street r’n’b,” rock’n’roll, and gospel. Yet Gordy was thinking long-term. He knew his audience would mature. Motown arrangers (Paul Riser, etc.), were inspired by Broadway musicals and the jazz orchestrations of Duke Ellington and George Gershwin. They hired musicians from the Detroit Symphony to bring elegance to “the chitlin’ circuit.”

Ray Charles had already merged “strings with street,” but his audience was older. The Beach Boys, Phil Spector, The Beatles, and a number of British Invasion pop/rock acts were already cherry-picking from musicals, classical, and the avant-garde (in some ways prophesying the “progressive rock era” when Keith Emerson would do Bartok, Bernstein, and boogie-woogie in one flash). However, their audience, huge as it was, was steered (mostly by the industry) into a generation gap.

By comparison, Motown was way more pro-active about the marriage of classical, jazz, pop/rock, and “soul music.” It showed in the diversity of the Motown audience. Look no further than the I HEAR A SYMPHONY album.

My dad bought the SYMPHONY album about the same time I was tuning into his copy of TOGETHER AGAIN by Ray Charles. Both records were played regularly around our house. Released February 1966, SYMPHONY is a seamless blend of r’n’b, standards, and pop, overtly based on classical motifs. The orchestral scores channel Copland, Debussy, Dvorak, Ellington, Gershwin, and Prokofiev.

To underline the point, The Supremes remade The Toy’s A Lover's Concerto, drawn from Bach's Minuet in G. Baroque and French Impressionism rock together in My World is Empty (another Number One hit). Unchained Melody has been subjected to many indifferent orchestrations, but not on SYMPHONY. In my own performances of Unchained Melody, my “head guide” is not The Righteous Brothers, but The Supremes.

The opening song on SYMPHONY is Stranger in Paradise (from the musical KISMET), based on Russian composer Alexander Borodin's Polovetsian Dances. I felt like “a stranger in paradise” when this record first entered my then-eight year old ears. I’d been exposed to classical through cartoons and my grandfather’s record collection, but it was SYMPHONY that focused my little mind on arrangements, production, and songwriting.

H-D-H were celebrated on the album liner notes. Buried on Side Two is an overlooked H-D-H gem, Any Girl in Love. The sophisticated, mid-tempo tear-jerker is bittersweet r’n’b alternating with rich, gospel 1/3/6 harmonies. In the refrain, Ballard and Wilson sing mind-bending diminished chords while Ross sings the melody with vivid honesty.

Say the name “Diana Ross” and you often get a reaction, but I remind people there are “three sides to every story” (same can be said for another one of my heroes, James Brown). Ross probably knows every pro and con to being “a diva.” That said, based on what I’ve read and stories heard from Motown musicians I’ve known, I perceive Ross as just another sufferer of Tortured Artist Syndrome. Her vocal technique and heart for constant learning has profoundly influenced my approach to singing.

“A feeling so divine, 'Till I leave the past behind. I'm lost in a world, Made for you and me…”

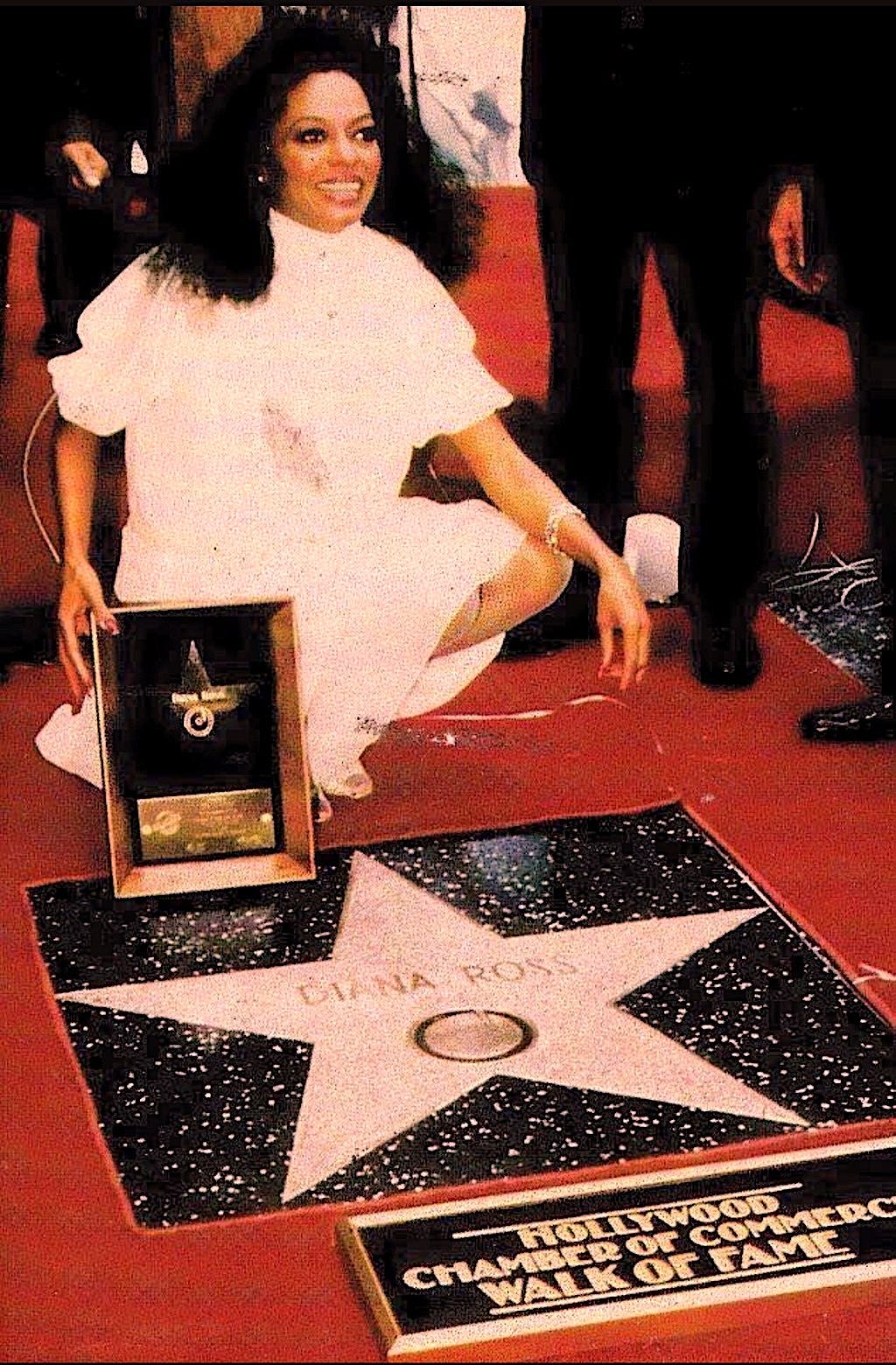

The cover of the SYMPHONY album shows three beautiful Supremes in white dresses, set against shadows and light. They’re talking to a dove, and their faces glow like they’re reading from a book of Psalms. This pastoral image, with the music, gave me serenity when I was growing up in Avis (Pennsylvania), an all-white semi-rural village. Motown, James Brown, and Ray Charles made me happy and want to play music. They were my first memorable contact with “black America” (via radio, records, and television).

The Civil Rights Movement was just something in the corner of my little eyes. I had no idea that skin color was a problematic issue until, a couple years later, I was finally exposed to examples of racial prejudice. It defied all logic I knew. It stung me as mindless, counter-productive, and a frustrating absurdity against God’s way of conducting the universe.

I was nine years old on that morning in April 1968 when Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. I cried. I was too young and removed from “the front” to get it all, but I could feel a loss, like someone of great bravery, determination, and presence had been snuffed out. I also felt like a stray bullet had gone through that pastoral image on that old Supremes album cover, boring a hole in my serenity.

Nowadays I believe that a symphony of serenity is being conducted in my heart. No bullet or worldly insanity can stop that symphony from playing.

“You bring much joy within, Don't let this feeling end, Let it go on and on and on…”

#dianaross #supremes #symphony #motown #johnnyjblair #singeratlarge #civilrightsmovement #racism #equality #berrygordy