California Dreaming With Sly Stone and Brian Wilson

A Chronicle of Their Soundtrack In My Life

Sun and skin tone are celebrated in The Golden State of California, named after Queen Califia, a mythological black woman. She tamed monsters, wore gold, ruled warriors, fought Christians before converting to Christ, and she was a 16th Century muse to artists, poets, and explorers who came here from Spain. Her soul is encrypted in the California Ethos, and last week we lost a pair of foremost emissaries for this Ethos: Sly Stone and Brian Wilson. With consummate innovation, both artists created songs that evangelized for the best of The West while forming “family bands”—Sly & The Family Stone and The Beach Boys—that sold millions of records and a California Dream.

Brian and Sly were possessed by visions of an ideal world, built on the youthful, optimistic template of 60s California. The freewheeling entrepreneurial spirit of Los Angeles was the setting for The Beach Boys to broadcast the delights of surf, cars, and romance, later expanding into a beloved panorama of a fulsome, transcendental America. Then, from the psychedelic pulpit of the San Francisco Bay Area, Sly & The Family Stone shouted out from a communal experiment in artistry, brotherhood, and motivational messaging. Both acts had a foundation in the church, merging gospel, doo-wop, jazz, pop, and rock’n’roll into a bold new vocabulary—and everybody can dance!

In 1965, The Beach Boys released the thematic TODAY! album. Side 2 was the “thoughtful side,” indicating Brian’s transition into orchestral pop and evocative lyrics. Side 1 was the “dance side,” kicking off with Dennis Wilson singing lead on “Do You Wanna Dance?” It was a cover of the hit song by Bobby Freeman, “San Francisco’s first rock star.” Freeman later collaborated with Sylvester Stewart a.k.a. Sly Stone (he got the name Sly due to a misspelling in grade school). Sly was marketing himself as a multi-instrumentalist and singer-songwriter while working as a DJ at KSOL radio.

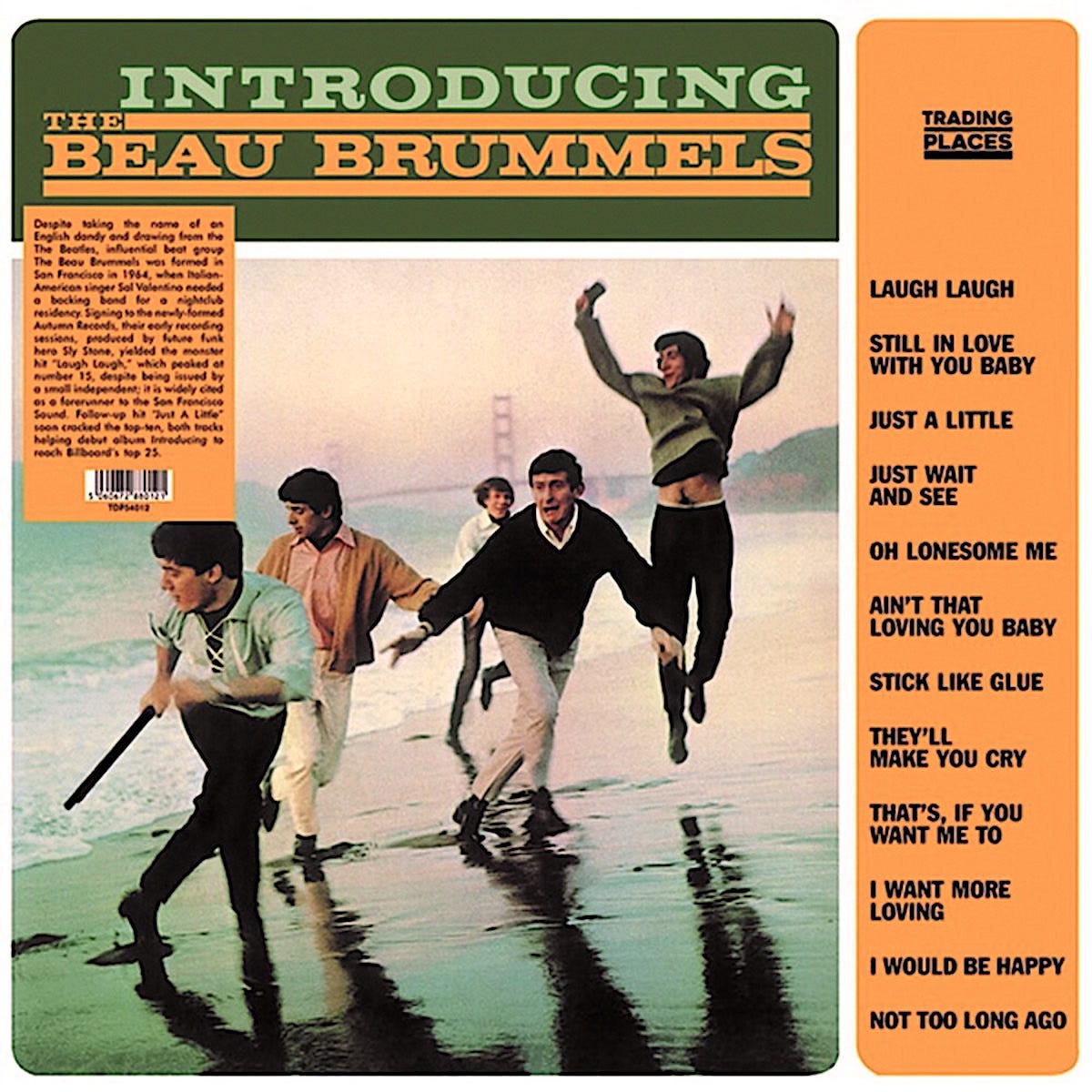

Sly’s ear for variety was rewarded when he was hired to produce The Beau Brummels, San Francisco’s folk-y comeback to The Beatles (jump to George Clinton’s comment that Sly & The Family Stone was “like a cross between The Beatles and Motown”).

California music, be it Beach Boys or the latest groups from Laurel Canyon and San Francisco, beamed across 3000 miles to our backwater Appalachian Pennsylvania village and into my childhood soundtrack. In 1966, my Dad (who was usually into jazz and R&B) brought home The Mamas & Papas LP with the bittersweet siren song “California Dreamin’”.

That same year, The Beach Boys woke the world with “Good Vibrations,” a sweeping transmission of a “blossom world” that also integrated the recording studio itself as “an instrument.” Chamber strings and electronica fused into a perfect pop 7” single that went to #1 with the presence of a cathedral. In one giant wave, artists and producers were forced to reset how they made records.

About a year later, Sly & The Family Stone hit the charts with “Dance To The Music.” Sly’s jubilant cheerleading rejoiced in music itself while instantly modernizing the genre of “soul music.” Literally within a week, artists on Motown and other black record labels pursued a funkier, edgier, and more psychedelic sound. On that note, Sly & The Family Stone was the first major label act to intentfully showcase mixed gender and multi-racial band members.

At age 12, my first profound California flashpoint was when my hipster cousin Pam loaned me a stack of 45s, including “Everyday People” by Sly & The Family Stone. It hit me like a sermon:

Released November 1968, Sly’s catchy foot stomper went to #1. The lyrics were an altar call to all shapes, sizes, income levels, and ethnicity, encouraging us to allow “different strokes for different folks” with the same heart that God accepts all of us. Part nursery rhyme and part urban gospel, Sly spoke to what puzzled me about the destructive, hateful, and illogical forces of prejudice and racism. I wanted no part of those forces, which weren’t hard to find in my environment.

God must’ve placed an angel to guard me from these influences and for me to look past the nominal religion I’d been exposed to and study true role modes of Christ. Like much of the world, I was rattled by the recent death of Martin Luther King—a preacher truly living out the words of Christ, following His mission statement in Luke 4:14-21 (recall that King was assassinated as he was planning a poor people’s march on Washington DC). In this context, Sly spoke to my confused, adolescent heart—and with a groovy beat. His messages were universal but clothed in the diversity of San Francisco. Prophetically, “Everyday People” was recorded in a San Francisco neighborhood where I’d eventually live.

Sly’s “moral purpose” continued with “Stand,” the title song from his million selling 1969 LP. Motivational tracks included “You Can Make It If You Try” and “I Want to Take You Higher” (a segue from earlier songs, including “Advice,” his collaboration with Billy Preston). Sly claimed “I Want To Take You Higher” was simply a dedication to music and the joy one gets from it but seeing him do it in the WOODSTOCK film took me higher. That night on August 17th, 1969, at 3AM, he uplifted the Woodstock audience with the love and nurturing he received growing up in the Church of God in Christ, made more apparent in the uncut DVD edition where Sly led the audience in chorus and “took it to church.”

The songs on the STAND album have been covered by many artists, and Sly & The Family Stone riffs have been name-checked and telegraphed by James Brown, Miles Davis, Jimi Hendrix, and countless others. From the STAND sessions came the 1970 hit single “Hot Fun In The Summertime,” highlighting Sly’s remarkable chord phrasing and Americana lyrics on par with Beach Boys salutes to amusement parks and summer fun.

Years later The Beach Boys covered “Hot Fun In The Summertime” with longtime associate Terry Melcher, who was friends with Sly. Terry was also son of a Hollywood icon, actress-singer Doris Day. Sometime in 1968, Terry introduced Sly to his famous mother, and she and Sly went to the piano and sang together.

Sly promised he’d record one of her songs, surfacing with a gospel-waltz take on “Que Sera Sera.”

STAND was inspirational in tone but revealed early signs of Sly’s disillusion with fame and a utopian 60s. He began his slide into drugs and paranoia while his band unraveled. In 1971 they released THERE’S A RIOT GOING ON (Sly played half the parts while experimenting with beatbox technology). It was a dark, controversial LP said to be Sly’s answer to Marvin Gaye’s landmark WHAT’S GOING ON album (itself prompted by a 1969 riot in the Bay Area). “Family Affair,” “If You Want Me To Stay,” and other hits kept coming but by the mid-70s, the classic line-up of the band was gone and Sly became famous for his “no shows” and frightening bipolar erraticism. His audience shrank as his later recordings recycled old ideas amidst random flashes of brilliance, curious collaborations, and short but dazzling comeback appearances. In his later years he chose a minimalist life of peace and sobriety.

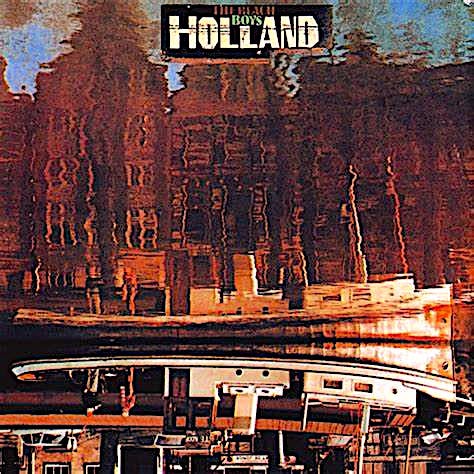

Rewind to 1973, The Beach Boys were in The Netherlands recording the HOLLAND album that brought them back to the charts with the single “Sail On Sailor.”

That year in Pennsylvania, my high school friend Collo Gerstenberg, a transplant from Germany, loaned me a copy of the Beach Boys 1970 masterpiece, SUNFLOWER. It was a logical sequel to the sublime songcraft and production of PET SOUNDS, fusing the band’s interests in ornate Gershwin-esque pop, soul/R&B, folk rock, and the uncategorizable, such as the chillwave futuristic invention of “All I Wanna Do”

At the time I was into jazz, glam, and progressive rock, and SUNFLOWER appealed to me more than the “car/surf” Beach Boys typecast I knew, with the irony that it took a European to get me to listen to an American band. SUNFLOWER was ardently studied by artists I admired (10cc, ELO/The Move, Queen, Yes). Unbeknownst to me, the European market for The Beach Boys flourished while their American audience declined after 1966, despite the artistic triumph of their PET SOUNDS album and salutes from The Beatles, Eric Clapton, and The Who.

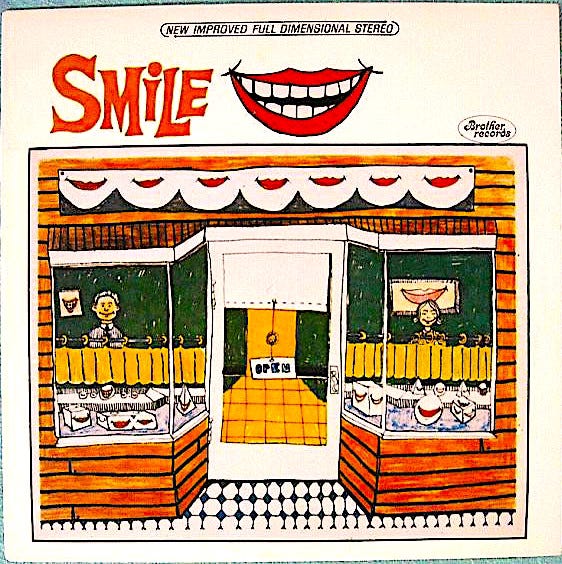

In 1967, THE Beach Boys made other career missteps as their highly anticipated SMILE project was abandoned.

It was to be “a teenage symphony to God” and an American art-statement that was previewed and praised by Paul McCartney and Leonard Bernstein, but Brian Wilson withdrew from SMILE and into an abyss of drugs and nervous breakdowns. The Beach Boys fell off the American “hipness radar” despite a a string of fascinating records that presaged garage band revivalism, electronic wizardry, and (now fashionable) lo-fi bedroom recording with “found objects.” One DJ called this period (1967-73) their “Lost Summer.”

During this “Lost Summer,” The Beach Boys created an innovative and sublime reflection of Americana—of young people empathizing with parents who’d survived the Great Depression and World War II, only to be faced with complex morality, rocket science, and rock’n’roll. The Beach Boys revived the “Cabin-Essence” of John Steinbeck and Mark Twain novels, the poems of Robinson Jeffers and the transcendentalists, Dustbowl folk singers and Delta bluesmen, American Indian legends, the myths of Baja and Mexicali, the photographs of Ansel Adams, the art of Albert Bierstadt, James Earle Fraser, and Frederic Remington (painter of “the Old West”), and even comic book icons like Captain America (“Heroes & Villains”). T-Birds, and 409’s were replaced by bicycles, boats, horses, stagecoaches, and trains. Surfing became a metaphor for nation and nature. The vertical wave was a chance to touch The Big Sky, then walk 40 days on that “Long Promised Road” to be divinely sculpted in sun baked canyons, out of the desert and into the ocean with golden skin. “Let The Wind Blow” the salt and sage mingled with dust made by the pioneers, drifters, grifters, and searchers who sought new life on the California horizon.

This “message” began to reach me after I moved to sun kissed Florida, then to New York to join a prog-rock band in summer 1975. Our bass player John Comerford came equipped with lots of gear and a fully stocked rock’n’roll van (like something out of “That 70s Show”) with cassette player. His cool stack of tapes included David Bowie, King Crimson, and HOLLAND, which intrigued me, but it was another year before I became a full-on Beach Boys fan (photo of me and Jeff Lloyd summer 1976):

One of my mentors, singer-songwriter and renaissance man Jeff Lloyd, turned me on to the double LP CARL & THE PASSIONS / PET SOUNDS. I’m not clear why Brother Reprise Records bundled those albums in 1972, but I was hooked! For the rest of my days, I studied every Beach Boys B-side, bootleg, broadcast, biography, solo project, and spin-off. Their influence permeated my original music, and I’ve covered many of their songs onstage. I became a walking encyclopedia and entire relationships formed around “all things Beach Boys.”

CARL & THE PASSIONS may be an odd jumping off point. Fans complained about it and for years it was ignored. The recording sessions were disjointed, the mixes were wobbly, and there were no hits, but something charmed me about it (Tom Petty said CARL is one of his favorites). On the plus side, the musicianship and vocals were superb, extending their interests in country rock, gospel, and R&B, on par with deep cuts by Crosby Stills Nash & Young or The Doobie Brothers. Dennis Wilson (then teasing a solo career) submitted stunning orchestral works. Blondie Chaplin and Ricky Fataar, both from South Africa, added a fresh “black Beatles” energy. Brian submitted two gems: “Marcella” (an ersatz sequel to “Surfer Girl”) and “You Need a Messa Help to Stand Alone,” a rowdy folk rocker with ecclesiastical poetry featuring the howling and crooning of Brian and Carl Wilson.

CARL set the stage for HOLLAND, a magnificent follow-up and my favorite Beach Boys LP.

In 1977, Jeff moved to California and invited me out to establish myself, but instead of L.A. as I expected, he’d set up in the San Francisco Bay Area. I took an apartment in the city, immersed myself in the punk/new wave scene, and worked part-time at a record shop on Haight Street. I befriended co-worker and mega-Beach Boys fan Greg Marriner, who fed me bootlegs and ephemera. Then the wackiest meeting ever happened.

In summer 1981, I was flying from San Francisco to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania to visit family and friends. While changing planes in Pittsburgh, imagine my surprise to see The Beach Boys entourage (minus Carl Wilson, who wasn’t on that tour) waiting at the gate, heading to a run-off gig in Harrisburg. I conversed at length with Brian Wilson, Bruce Johnston, Al Jardine, Mike Love, and Dennis Wilson. During the flight, they let me pick their brains about songs, studio craft, songwriting, etc.—my opener was to talk about “Celebrate the News.”

As we looked out the plane windows, Al was very interested in the landscape. It occurred to me to compare Appalachia to Big Sur as my brain processed this enigma of meeting these quintessential Californians here in Pennsylvania. A few years later, back in CA, I was demo’ing on the keyboard, feeling homesick for my native PA. Out of nowhere the line “(I Wanna Be-in) Pennsylvania” flew into my head, modeled after American landmark songs made by The Beach Boys.

In 1985 I released my first LP, DOOR IN THE WATER, a theme album drenched in Beach Boys influence (the title song borrowed a riff from “Wild Honey”). In the build-up to DOOR, I befriended fellow musician Mike Roe of The 77s. He’s one of my heroes (then and now) and a total Beach Boys nut. We’d gab for hours on the phone, and our future collaborations on record indicate our influences.

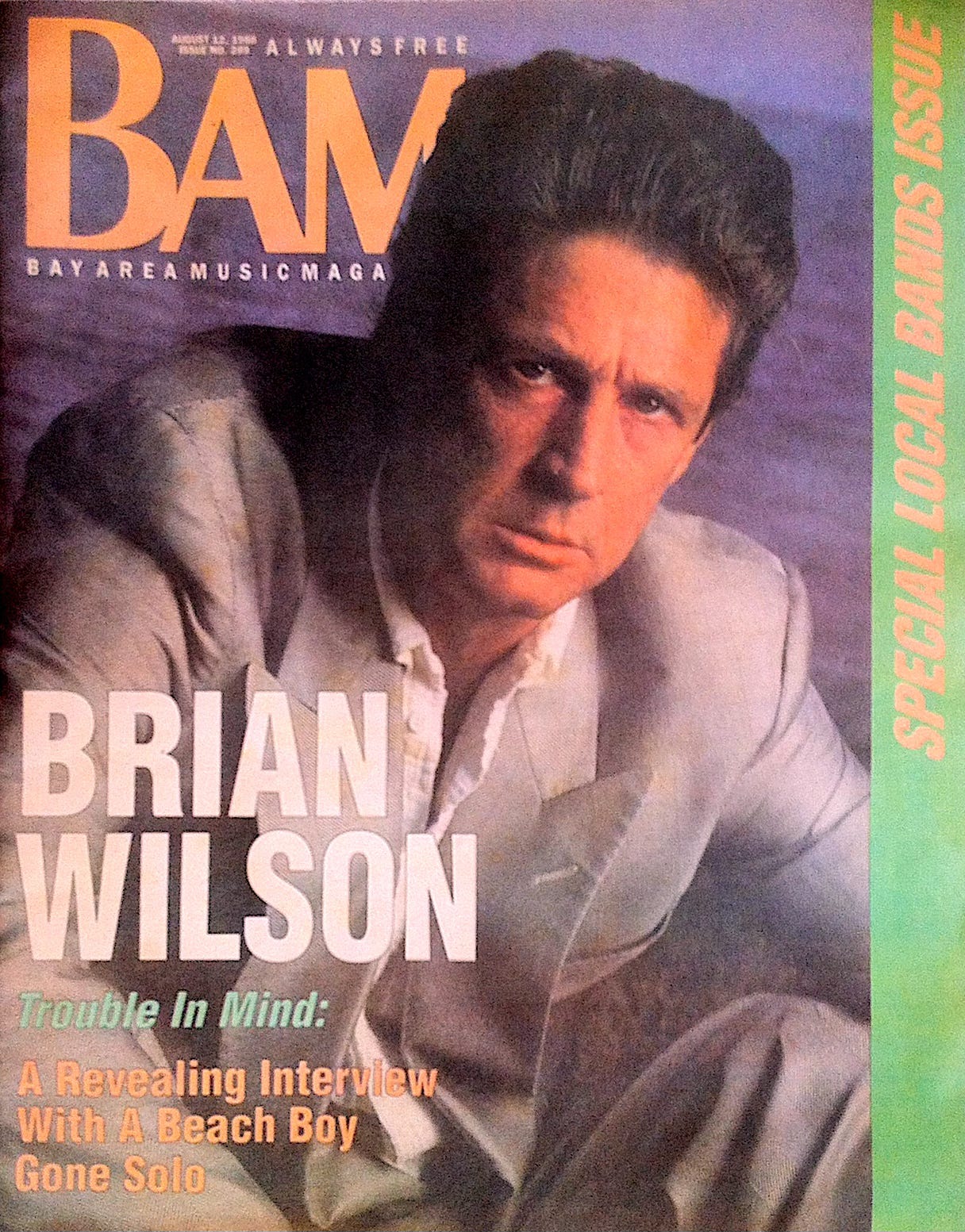

The buzz in 1988 was Brian plotting his first real solo album, and with full industry back-up—which meant touring. I muscled my showbiz connections and applied to be a bass player in Brian's road band. My application was earmarked by affirmative phone conversations with Andy Paley (Brian's then-collaborator) and an audition tape, to which Brian listened and gave encouraging feedback (to this day I gush with humble gratitude for what he said). Then, seeming to underscore my wishes, BAM magazine gave me a micro-feature with Brian on the cover. It looked like God's synchronicity but, not only did I not get the bass gig, Brian’s comeback was short-circuited by ongoing dramas with his mental state and business affairs. The subtitle of this magazine cover describes the real outcome.

Brian’s released the single “Love & Mercy,” which became an anthem and a song I added to my solo acoustic set. Sometime after that I wrote “Dumb Angel” based on a dream I had about growing up in Pennsylvania and being visited by Lewis Carroll, Elvis Presley, and Brian Wilson at a church.

Because of discouragement and problems I was having in California, I moved my family “back home” to central Pennsylvania in 1991. There I worked to hard to find a new path, rebuilding my professional life with employment in recording studios and music stores while subbing with different bands, including The Acapulco Soul Surfers with 2 black guys and 2 white guys (one could sing in Spanish). Our set list was Latin Rock, surf rock, and classic soul—including six Sly & The Family Stone covers! Our band lasted but four gigs, but friendships endured and set the stage for me to join a “black church” for 4 years. Under the lead of the pastor’s wife, I joined the worship group as a creative liaison empowered by the love of Jesus. The group played events around the region and made recordings I’m still proud of. They were a key part of my FIRE album with my cover of “Everyday People,” which featured legendary drummer Jab’O Starks of James Brown fame (I’d performed a short string of gigs with Jab’O and Clyde Stubblefield). Released in 2000, FIRE was a trans-national production, and “Everyday People” encapsulated my relationships and my commitment to speaking out against racism and living a life based on Christ’s example.

In the background Brian’s comeback efforts finally took root, starting in 2004 with his revisitations of PET SOUNDS, reviving SMILE, and a string of acclaimed solo albums with his new band. In 2007 he built a concept album around the pop standard “That Lucky Old Sun” (which I’ve since added to my solo set), and California started to call me again.

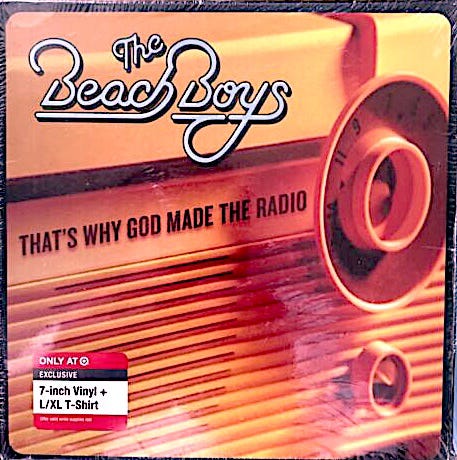

My assignment in Pennsylvania wound down in 2009 and, after touring internationally as a bassist with The Monkees, I moved back to San Francisco in 2011. Then I had an economic and spiritual crash in 2012—the year The Beach Boys reformed and made a hopeful new album with a God subtext.

I bottomed out in a binge of carnal torments and alcohol before I entered 12-Step Recovery and got back on track with God, healing, right relationships, and a renewed heart for service.

Bookending my progress are “Love & Mercy” and “Stand.”

In a sort of cosmic pun, Brian and Sly died within days of one another. They were both 82, beating the longevity odds after a lifetime of torments with physical health, mental illness, temptations of the age, and the burden of living up to the “genius” label. Yet they emerged on their own terms, with dignity, grace, and with a musical legacy that continues to enrich people around the world.

The day after Brian died, a pair of California poppies (our state flower) bloomed for the first time in an unattended patch of ground near our house, reminding me that our music plays long after we leave this mortal coil.

#beachboys #brianwilson #slystone #slyandthefamilystone #soundtrack #dumbangel #johnnyjblair #singersongwriter #americana #california #pennsylvania