Boys, Girls, Guitars, & Sister Rosetta Tharpe

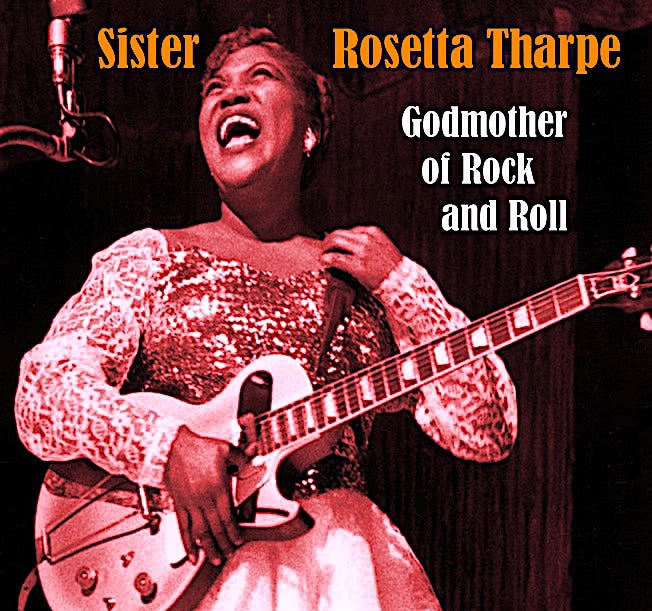

Birthday shout-out to The Godmother of Rock & Roll and Original Soul Sister

“Electric guitar gets run over by a car on the highway

This is a crime against the state

This is the meaning of life. To tune this electric guitar”—Talking Heads

Wearing eyeglasses doesn’t mean I’m smarter, and playing electric guitar doesn’t mean I’m more manly. Yet, in this day and age, throughout most of the world, the electric guitar has become a sort of Techno-phallus, a symbol of male musical power for legions of “air guitarists.” It empowers music store tinkerers of Nirvana riffs and Stairway to Heaven. It brings rapture to players with the dexterity, zeal and skill to make the instrument speak at any decibel. However, if you scan back through history, the guitar (a descendent of the gittern, the lute, and the psaltery) was propagated mainly by women. Male dominance of guitar is a recent development.

Male academia (from the Renaissance to Romantic eras) mostly suppressed female composers and instrumentalists, but art galleries carry more images of women than men on guitars. Outside of Spanish flamenco culture, the guitar was regarded as a “ladies parlor instrument” in Europe and the New World. In early 20th Century America, men were more likely to get down on brass and wind instruments, banjo, ukulele, or 4-string tenor guitar than on the standard 6-string (Groucho Marx’s 1932 tenor guitar scene in the film HORSE FEATHERS made a fashion statement, and Groucho had chops).

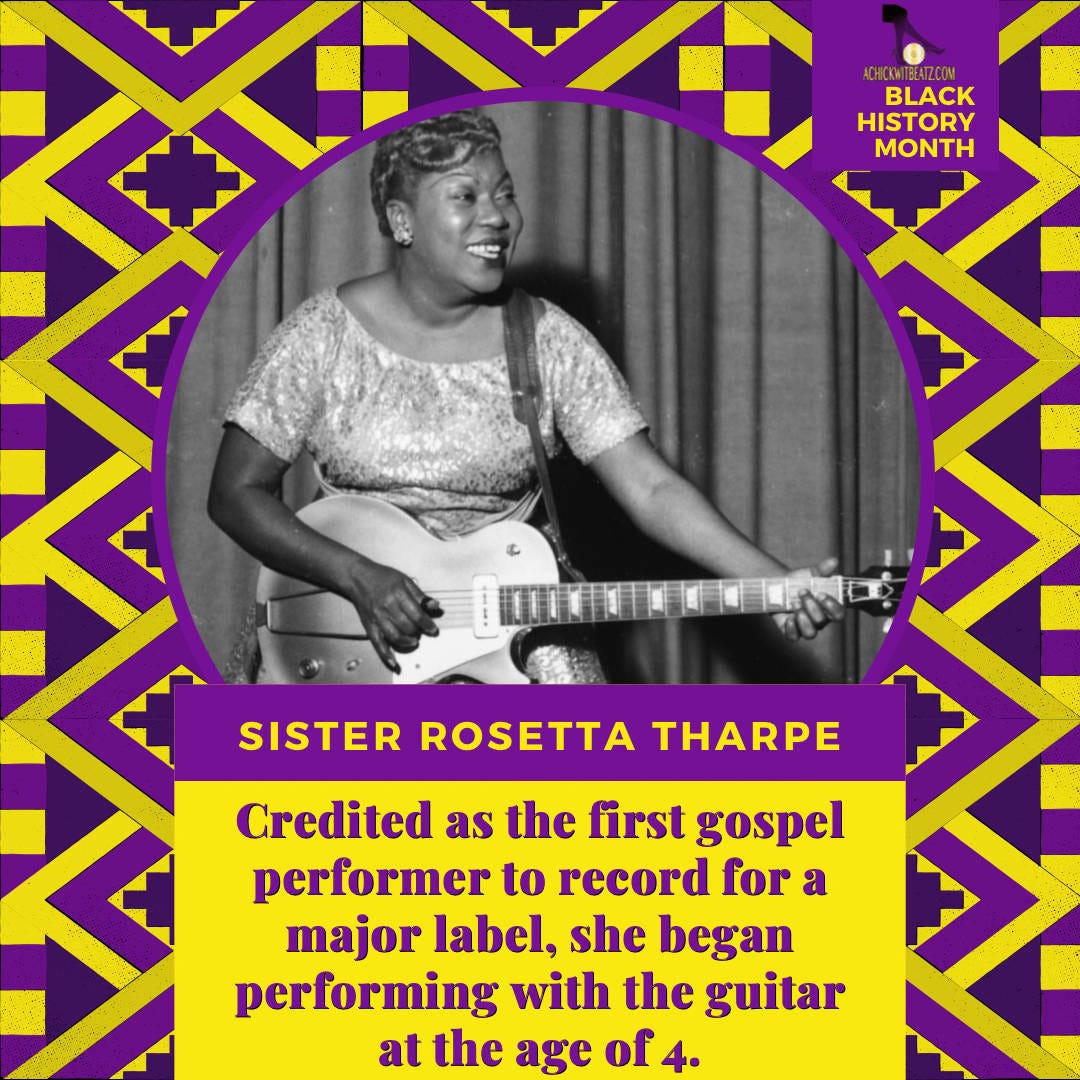

For a few decades prior to the 50s, guitar was an equal opportunity employer, particularly in blues and hillbilly music, where picking duties were split evenly between the sexes. Into this level playing field came Sister Rosetta Tharpe, a black gospel singer-songwriter and unsung pioneer of the electric guitar.

“…this woman was playing a different kind of music. It was gospel, but the way she put it across, in her bluesy-jazzy style, was a real revelation, and she looked like something else too…it was only later that I realized she played guitar kind of like T-Bone Walker, in a real ‘bad’ groove.”—Etta James

In the late 1940s, electricity and technology gave the guitar a makeover, empowering it with astonishing dynamics and range. Tharpe (1915-73) was trained on keyboard and played guitar fluently with alternate tunings. She joyfully embraced the electric and was one of the early proponents of Gibson’s solid body models. In the 40s and early 50s, while Les Paul was using the guitar as a recording device, and blues and country players kept to a limited scrim, Tharpe tested amplifier tone colorings, sustain and overdrive well before rockabilly-seer Dorsey Burnette and British Invasion rockers claimed to have “invented distortion” and “discovered feedback.”

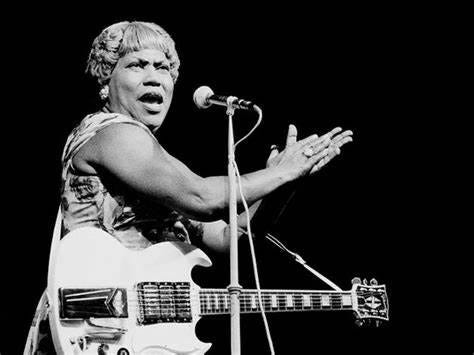

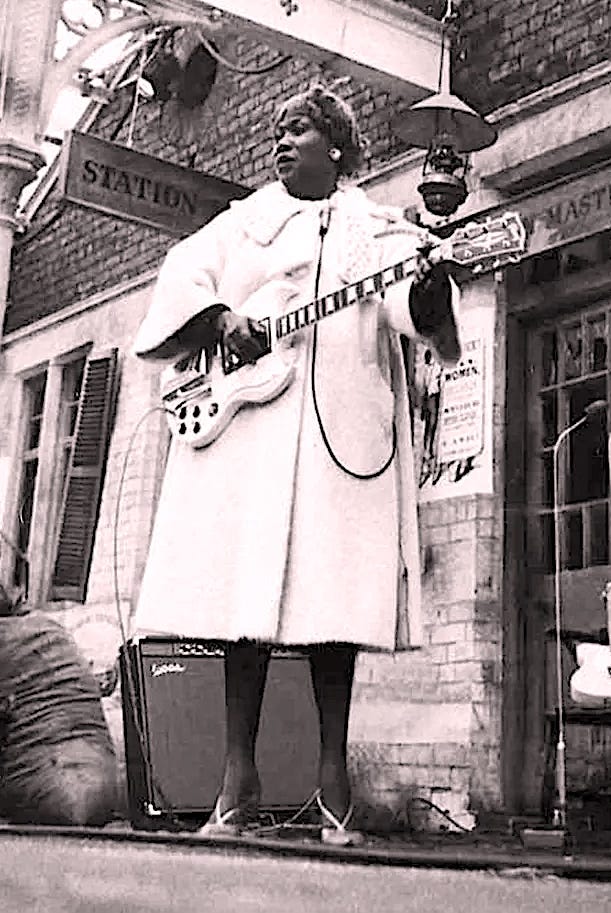

Tharpe was duck-walking, arm-propelling and playing behind her head years before Chuck Berry, Jimi Hendrix and Pete Townshend took the stage. Memphis Minnie and others may have plugged in before Tharpe, but it was Tharpe who joined a breed who “made the guitar talk” as a lead instrument, and she liked to play it loud!

When a British interviewer asked Tharpe if it was “strange to worship God with a guitar,” she replied, “I am what you call an autodidact. I play loud because I want to express my happiness in the Lord!…in my church…we like to worship Him with all the instruments. Gospel music should be noisy!”

Like Louis Jordan, Tharpe was an unsung and unwitting trailblazer for rock’n’roll, if for both musicianship and showmanship. She made the most of lighting, staging and wardrobe, giving audiences a rush of exuberance and movement when most gospel singers were staid and stiff.

“There is nothing like a friendly, warm audience. It makes you feel that what you are doing and saying is reaching inside people.”—Sister Rosetta Tharpe

One beauty about rock’n’roll is the unconstrained way musicians can sample any style of music and rivet it to basic melodic and rhythmic instincts. She mixed it up with Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, Lena Horne, Little Richard (who she “discovered” and advanced his career), and country star Red Foley. In her eclectic career ride, Tharpe headlined at Carnegie Hall, The Grand Old Opry, and any church or night club in between. Thematically, however, she never stopped singing straight gospel songs or lyrics that didn’t harmonize with Biblical truths and a view of the eternal.

“She was so strong in her convictions…she just believed that what she was doing was what God had given her.”—Ruth Brown

The illusory battle between the sacred and the secular was a minor distraction to Tharpe. David Livingstone, the British explorer-missionary, felt God had called him to be an explorer first, and a missionary second. This echoed Tharpe’s mentality. In other ways her career arc resembled Blind Willie McTell, a street-preaching 12-string picking gospel-blues singer who circled the music world on his own terms. However, the sacred vs. secular storm did weigh on Tharpe’s livelihood. She came from a Pentecostal background and, to Pentecostals, crossing over was an offensive compromise of “church purity,” and playing guitar was “unladylike.” On the flipside, crowds at nightclubs like The Apollo (where Sam Cooke would watch her in awe) weren’t always ready for gospel songs. Nonetheless, Tharpe won fans with her unwavering passion and prowess.

“We took the church to the nightclubs because the people in the clubs weren’t coming to church.”— Roebuck “Pops” Staples

Whether because of “religious controversy,” or the “boys club” mentality of showbiz, or erratic label support, Tharpe has been downplayed in music history. Her legacy was overshadowed by her contemporaries, Clara Ward and Mahalia Jackson (who sold millions and had better record label backing). Tharpe’s body lies in an unmarked grave in Philadelphia (where there are now annual Tharpe festivals), but her name has not been lost on the movers and shakers of the field.

In November 1956, when Jerry Lee Lewis auditioned for Sun Records, he warmed up with Tharpe’s song, Strange Things Happening Everyday.

Later he said that the phrase “great balls of fire” came to him after seeing Tharpe in concert at a church in Natchez, Mississippi. In 2005, Lewis told journalist Peter Guralnik, “…There’s a woman that can sing some rock and roll…she’s singing religious music, but she is singing rock and roll. She’s shakin’ man…she jumps it. She’s hitting that guitar and she is singing! I said, ‘Whoooo.’ Sister Rosetta Tharpe.”

During the legendary “Million Dollar Quarter” sessions of December 1956, Lewis joined Johnny Cash, Elvis Presley and Carl Perkins to jam on Tharpe’s arrangements of Down by the Riverside and Peace in the Valley. “Elvis loved Sister Rosetta Tharpe,” said Gordon Stoker of The Jordanaires, who clocked in thousands of hours with Presley. “Not only did he dig her guitar picking, but he loved her voice.”

After seeing Tharpe live in 1960, Johnny Cash called it one of “the most moving experiences of his life.” Daughter Roseanne Cash said (on LARRY KING LIVE) that Tharpe was “likely my father’s most favorite artist.” As with Lewis, Tharpe’s song Strange Things Happening Everyday was a touchstone with Cash and Perkins, who said, “It was my Dad’s favorite song. When Sister Rosetta had it out, that’s one of the things I’d try to learn how to play…When people would come to our house on Sundays, I’d always take my little guitar and play (that song). It was rockabilly, that was it…it was.”

During the 50s and 60s, Tharpe’s star dimmed in America, but in England she got a second wind with young Brits fascinated by American roots music. Ginger Baker “absolutely loved her” after backing her on a U.K. tour. Jeff Beck, Brian Jones, and Keith Richards “freaked” when they heard her. Go Now-period Moody Blues covered her songs in their live set, John Lennon name-checked her during the LET IT BE sessions, and Eric Burdon remains a devoted fan.

Aretha Franklin, Isaac Hayes, Little Richard, and The Staple Singers identified Tharpe as a vital influence on their careers. Robert Plant dueted with Alison Krauss to record Sister Rosetta Goes Before Us, written by Sam Phillips (ex-wife of T-Bone Burnett). The Alabama 3 (SOPRANOS TV theme) and The Noisettes have named songs after her. Bob Dylan airs her often on his satellite radio show, and his electric material channels Tharpe’s “talking blues” phrasing and band arrangements.

“I didn’t find out about her until the late 60s, early 70s. Rosetta Tharpe was a righteous and very, very powerful musician.”—Bonnie Raitt

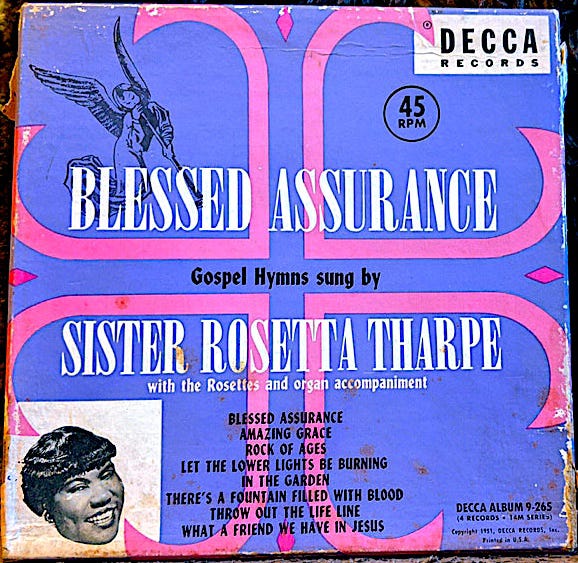

In 1980, I was working in a record store on Haight Street (San Francisco). While prepping a load of orphaned disco records for the trash, I found a book of playable 78s by the Golden Gate Quartet (another Presley favorite) and a set of pristine-condition 45s in a boxed set called BLESSED ASSURANCE by Sister Rosetta Tharpe. This castaway was a fitting introduction for me. Singlehandedly, Tharpe taught me that there are no holds barred in how to remake a standard.

Oddly, Tharpe doesn’t play guitar on this Decca session; it is barely mentioned in Gayle F. Wald’s 2008 biography. Backed by The Rosettes, the 1951 session yielded radical remakes of spirituals with moody vocals, dreamy organ, and whispery percussion.

Tharpe’s arrangement of Amazing Grace sounds improvisational and spontaneous. The melody line is transformed into a blue-note call-and-response. Instead of doing “Amazing grace how sweet the sound” in the traditional sequence ending on the 5th, she elongates “amazing,” sliding from the 3rd for “aaaaa,” to the 5th, holding the “maaaaaazing.” “How” is given a mouthful of the downbeat, and she puts breath-breaks in unlikely places. The word “sound” is held out, like the word has its own significance. The remaining verses are handled the same way.

The song, with its easily managed melody, has been sung by thousands and has been restyled in everything from jazz to metal. However, in my estimation, Tharpe’s interpretation heightens the essence of a song written by John Newton, an ex-slave trader who repented and became an evangelist and anti-slavery activist. Tharpe knew the burdens of controversy. She knew that innovation and mold-breaking don’t always translate into mass popularity. Neither does talk of salvation.

#sisterrosettatharpe #electricguitar #christian #gospel #arkansas #philadelphia #birthday